Annotation:Lillibulero: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (27 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{TuneAnnotation | |||

|f_annotation='''LILLIBULERO''' AKA and see - {{#show:Lillibulero|?Is also known as}}." English, Irish; Air (6/8 time) or Jig. England, Northumberland. A Major (Cole, Haverty, Miller & Perron, Raven, Sweet): B Flat Major (Manson): G Major (most versions): D Major (Chappell, Scott). Standard tuning (fiddle). AB (Cole, Raven, Stanford/Petrie, Thompson): AAB (Chapell, Haverty, Scott): ABB (Sharp): AABB (Barnes, Merryweather, Miller & Perron, Seattle, Sweet): AABBCCDD (Oswald). The the words of the chorus or burden of the song, ''lero, lero, lillibulero bullen-a-lah,'' purportedly were, according to a contemporary (Protestant) chronicle quoted by the English musicologist Chappell (1859), Irish Gaelic "words of distinction used among the Irish Papists in their massacre of Protestants in 1641." | |||

'''LILLIBULERO''' | |||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

"Lillibulero," Chappell goes on to say, was an anonymously composed Whig tune (i.e. joined to various anti-Catholic words) and the British army's song during the Revolution of 1688 in which William of Orange defeated James II. A "party tune," includes Kidson (1922), which was disseminated on the authority of Bishop Burnet. It was immensely popular from the time of its introduction and not a little influential from a political standpoint as it was used as a rallying call for the Protestants | Other suggestions for the meaning of the burden are that it was a stage convention for "foreigner's dialect" used in 17th century English plays to denote unfamiliar languages. Another explanation is that it is a corruption of the Gaelic phrase ''An lile ba léir é; ba linn an lá,'' which translates as "The (Orange) lily was (the most) evident; we carried the day," which would fit with the political associations of the song. | ||

{{break|2}} | |||

"Lillibulero," Chappell goes on to say, was an anonymously composed Whig tune (i.e. joined to various anti-Catholic words) and was the British army's song during the Revolution of 1688 in which William of Orange defeated James II. A "party tune," includes Kidson (1922), which was disseminated on the authority of Bishop Burnet. It was immensely popular from the time of its introduction and not a little influential from a political standpoint as it was used as a rallying call for the Protestants. | |||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

In fact, "Lillibulero" has been called the "tune that drove James out of three countries" (i.e. England, Scotland and Ireland). Pepys says: "Slight and insignificant as (the words) may now seem, they had once a more powerful effect than either the Philippics of Demosthenes or Cicero; and contributed not a little towards the great revolution in 1688." It was played by the Williamites (followers of William of Orange who became William III of England) during the Irish War of 1689–1691 and very probably at the battle of the Boyne, according to Winstock (1970). Johnson (Stenhouse ed.) asserts that the tune was derived from "[[Jumping Joan]]" (AKA "[[Joan's Placket is Torn]]"), but Bayard (1981) and Glen disagree. | |||

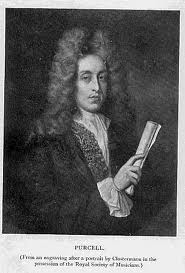

The English composer Henry Purcell has been credited with the tune, often described as one of his harpsichord lessons. It was ascribed to him by Playford (1689) and especially later by Chappell (1859), but other musicologists believe there is little direct evidence for this and it is more likely that it was a simply a folk tune; Kidson (1922) states simply the tune was arranged by Purcell for a printing in 1686. | {{break|2}} | ||

< | The English composer Henry Purcell has sometimes been credited with the tune, often described as one of his harpsichord lessons. He also used it in his stage work '''The Gordian Knot Untyed'''. It was ascribed to him by Playford (1689) and especially later by Chappell (1859), but other musicologists believe there is little direct evidence for this and it is more likely that it was a simply a folk tune; Kidson (1922) states simply the tune was arranged by Purcell for a printing in 1686. Dancing master Thomas Bray included it as the bass in the melody for his country dance "[[Short and Sweet (3)]]," printed in '''Thomas Bray's Country Dances''' (1699, p. 32). There can be no doubt the tune was well-known in the 17th century, as it is referenced in period literature. Emmerson (1971), for example, reports a description from 17th century literature of a scene in London: | ||

[[File:purcell.jpg|250px|thumb|left|Henry Purcell (1659-1695)]] | |||

<blockquote> | |||

''Some were dancing to a bagpipe; others whistling to a Base Violin,'' | ''Some were dancing to a bagpipe; others whistling to a Base Violin,'' | ||

''two Fiddlers scraping Lilla burlero, My Lord Mayor's Delight, upon'' | ''two Fiddlers scraping Lilla burlero, My Lord Mayor's Delight, upon'' | ||

''a couple of Crack'd Crowds.'' | ''a couple of Crack'd Crowds.'' | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

Regarding the lyrics, Chapell reports they were ascribed to Lord Wharton and Lord Dorset, but he thinks neither likely to have written them. The words satirize the Irish Jacobite Richard Talbot, Duke of Tyrconnell, and King James' agent in Ireland who was a key figure in the intrigues for returning James to power and involving the French in the struggle for Irish freedom (he ended his life as an exile in France). Though the song appears in numerous publications, Chappell found the earliest printing to be in a collection called '''The Muses' Farewell to Poetry and Slavery''' (1689). There is an old song called "There Was an Old Fellow at Waltham Cross" that uses a combination of strains sounding like both "Lillibulero" and "Dargason;" "Waltham Cross" was published in 1640 and Bayard (1981) thinks this suggests evidence of the existence of both "Lillibulero" and "[[Dargason]]" before the 1680's | Regarding the lyrics, Chapell reports they were ascribed to Lord Wharton and Lord Dorset, but he thinks neither likely to have written them. The words satirize the Irish Jacobite Richard Talbot, Duke of Tyrconnell, and King James' agent in Ireland who was a key figure in the intrigues for returning James to power and involving the French in the struggle for Irish freedom (he ended his life as an exile in France). | ||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

Though the song appears in numerous publications, Chappell found the earliest printing to be in a collection called '''The Muses' Farewell to Poetry and Slavery''' (1689). There is an old song called "There Was an Old Fellow at Waltham Cross" that uses a combination of strains sounding like both "Lillibulero" and "[[Dargason]];" "Waltham Cross" was published in 1640 and Bayard (1981) thinks this suggests evidence of the existence of both "Lillibulero" and "[[Dargason]]" before the 1680's. | |||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

Early versions of the air were published in Henry Playford's '''The Second Part of Music's Handmaid''' (1689 as "A new Irish tune"), Robert Carr's '''The Delightful Companion, or Choice New Lessons for the Recorder or Flute''' (1686), set for keyboard by Purcell in '''Musick's Handmaid''' (1689 as "A new Irish tune"), D'Urfey's '''Pills to Purge Melancholy,''' as the bass of 'Jig' in '''The Gordian Knot Untied''' (1691) and John Gay's '''The Beggar's Opera''' (1729, where it appears under the title "[[Modes of the court so common are grown (The)]]") and numerous other ballad operas. Alternate songs set to the tune include "Dublin's Deliverance; or, The Surrender of Drogheda" ('''Pepys Collection'''), "Undaunted London-derry; or, The Victorious Protestants' constant success against the proud French and Irish forces" ('''Bagford Collection'''), "The Courageous Soldiers of the West" ('''Bagford Collection'''), "The Reading Skirmish" ('''Bagford Collection'''), "The Protestant Courage" ('''Roxburghe Collection'''), and "Courageous Betty of Chick Lane" ('''Roxburghe Collection'''). | |||

{{break|2}} | |||

The version of the words ascribed to Wharton begins: | The version of the words ascribed to Wharton begins: | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

''Ho Brother Teaghe, dost hear de decree?''<br> | ''Ho Brother Teaghe, dost hear de decree?''<br /> | ||

''Lillibulero, bullen a la,''<br> | ''Lillibulero, bullen a la,''<br /> | ||

''Dat we shall have a new Deputie.''<br> | ''Dat we shall have a new Deputie.''<br /> | ||

''Lillibulero, bullen a la''<br> | ''Lillibulero, bullen a la''<br /> | ||

''Lero, lero, Lillibulero,''<br> | ''Lero, lero, Lillibulero,''<br /> | ||

''Lillibulero, bullen a la''<br> | ''Lillibulero, bullen a la''<br /> | ||

''Lero, lero, lillibulero''<br> | ''Lero, lero, lillibulero''<br /> | ||

''Lillibulero, bullen a la.''<br> | ''Lillibulero, bullen a la.''<br /> | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

In '''Songs of the British Isles''', author Jerry Silverman reports that as late as the American Civil War the English musicologist Francis James Child used the tune for another satire, called "Overtures from Richmond" which ridiculed the Jefferson Davis and the Confederacy. | In '''Songs of the British Isles''', author Jerry Silverman reports that as late as the American Civil War the English musicologist Francis James Child used the tune for another satire, called "Overtures from Richmond" which ridiculed the Jefferson Davis and the Confederacy. | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

</ | From at least the 19th century, the air of "Lillibulero" has been attached to the song "The Protestant Boys," by which name it is most commonly known among Orange flute band members in Ireland's north. | ||

< | <blockquote> | ||

'' | ''The Protestant boys are loyal and true,''<br /> | ||

<br> | ''Stout-hearted in battle and stout-hearted too,''<br /> | ||

<br> | ''The Protestant boys are true to the last,''<br /> | ||

</ | ''And faithful and peaceful when danger is past,''<br /> | ||

< | ''And oh!, they bear and proudly wear,''<br /> | ||

'' | ''The colours that floated o'er many a fray,''<br /> | ||

''Where cannon were flashing and sabres were clashing,''<br /> | |||

''The Protestant boys still carried the day.''<br /> | |||

</blockquote> | |||

See also Welsh violinist John Thomas's c. 1752 variant entered in his music manuscript collection under the title "[[Bili Bylero]]"<ref>Thomas is sometimes referred to as "Alawon John Thomas", but the Welsh work ''alawon'' means 'melodies', as in 'John Thomas's Melodies'. </ref>. | |||

|f_printed_sources=Aird ('''Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs, vol. 2'''), 1785; No. 481. Aird ('''Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs, vol. 3'''), 1788; Glasgow, 1788, No. 481, p. 186. Barnes ('''English Country Dance Tunes, vol. 1'''), 1996. Chappell ('''Popular Music of the Olden Time, vol. 2'''), 1859; p. 58. Cole ('''1000 Fiddle Tunes'''), 1940; p. 52. '''Harding Collection''' (1915) and '''Harding Original Collection''' (1928), No. 197. Haverty ('''One Hundred Irish Airs, vol. 2'''), 1858, No. 162, p. 73. Jarman and Hansen ('''Old Time Dance Tunes'''), 1951; p. 64. ''JIFSS'', XV, p. 13. Kerr ('''Merry Melodies, vol. 2'''), c. 1880's; No. 213. Kerr ('''Merry Melodies, vol. 4'''), c. 1880's; No. 228. Kirkpatrick ('''John Kirkpatrick's English Choice'''), 2003; p. 11. Manson ('''Hamilton’s Universal Tune Book, vol. 2'''), 1846; p. 7. Merryweather ('''Merryweather's Tunes for English Bagpipes'''), 1989; p. 45 (two versions). Miller & Perron ('''New England Fiddler's Repertoire'''), 1983; No. 14. Moffat ('''202 Gems of Irish Melody'''), p. 79. O'Lochlainn ('''Irish Street Ballands'''), 1939; No. 36. O'Neill ('''Music of Ireland: 1850 Melodies'''), 1903; No. 19. Oswald ('''Caledonian Pocket Companion, vol. 7'''), 1760; p. 13. Raven ('''English Country Dance Tunes'''), 1984; p. 63. '''Ryan's Mammoth Collection''', 1883; p. 79. Scott ('''English Song Book'''), 1926; p. 6. Sharp ('''Country Dance Tunes'''), 1911–1922; Set VIII, p. 19. Seattle/Vickers ('''Great Northern Tune Book, part 2'''), 1987; No. 373 (appears as "Lilly Bullery"). Sharp ('''Country Dance Tunes'''), 1909; p. 56. Stanford/Petrie ('''Complete Collection'''), 1905; No. 503, p. 127. Neil Stewart ('''Select Collection of Scots, English, Irish and Foreign Airs, Jiggs & Marches, vol. 1'''), 1784; p. 2 Sweet ('''Fifer's Delight''') 1964/1981; p. 22. Thompson ('''The Hibernian Muse'''), c. 1770–1790; No. 77, p. 48. Walsh ('''Compleat Country Dancing Master, vol. 1'''), 1731; No. 38. | |||

|f_recorded_sources=RCA 09026-60916-2, The Chieftains – "An Irish Evening" (1991). | |||

|f_see_also_listing=Jane Keefer's Folk Music Index: An Index to Recorded Sources [http://www.ibiblio.org/keefer/l06.htm#Lil] | |||

|f_tune_annotation_title=Lillibulero | |||

}} | |||

Jane Keefer's Folk Music Index: An Index to Recorded Sources [http://www.ibiblio.org/keefer/l06.htm#Lil] | |||

Latest revision as of 01:59, 11 February 2022

X:1 T:Lilli Bulero M:6/4 L:1/8 B:Playford - Dancing Master vol. 8 (London, 1690, p. 216) Z:AK/Fiddler's Companion K:G V:1 clef=treble name="1." [V:1] G3AG2 B4B2|A3BA2 c6|B2d2G2 c4B2|A2G2F2 G6:| |:g4f2 g4d2|=f4f2 e4d2|e2f2g2 g4d2|e2d2B2 A6| e2d2c2 B2c2d2|e2e2c2 B2c2d2|e2e2B2 c4B2|A2 G2 F2 G6:|]

LILLIBULERO AKA and see - Irlandais Jig, Lilly Bullery, Lillie Bulairie, Lillie Bulera, Lilliburlero, My Lord Mayor's Delight, My Thing is My Own, Old Woman Wither so High?, Protestant Boys, Short and Sweet (3)." English, Irish; Air (6/8 time) or Jig. England, Northumberland. A Major (Cole, Haverty, Miller & Perron, Raven, Sweet): B Flat Major (Manson): G Major (most versions): D Major (Chappell, Scott). Standard tuning (fiddle). AB (Cole, Raven, Stanford/Petrie, Thompson): AAB (Chapell, Haverty, Scott): ABB (Sharp): AABB (Barnes, Merryweather, Miller & Perron, Seattle, Sweet): AABBCCDD (Oswald). The the words of the chorus or burden of the song, lero, lero, lillibulero bullen-a-lah, purportedly were, according to a contemporary (Protestant) chronicle quoted by the English musicologist Chappell (1859), Irish Gaelic "words of distinction used among the Irish Papists in their massacre of Protestants in 1641."

Other suggestions for the meaning of the burden are that it was a stage convention for "foreigner's dialect" used in 17th century English plays to denote unfamiliar languages. Another explanation is that it is a corruption of the Gaelic phrase An lile ba léir é; ba linn an lá, which translates as "The (Orange) lily was (the most) evident; we carried the day," which would fit with the political associations of the song.

"Lillibulero," Chappell goes on to say, was an anonymously composed Whig tune (i.e. joined to various anti-Catholic words) and was the British army's song during the Revolution of 1688 in which William of Orange defeated James II. A "party tune," includes Kidson (1922), which was disseminated on the authority of Bishop Burnet. It was immensely popular from the time of its introduction and not a little influential from a political standpoint as it was used as a rallying call for the Protestants.

In fact, "Lillibulero" has been called the "tune that drove James out of three countries" (i.e. England, Scotland and Ireland). Pepys says: "Slight and insignificant as (the words) may now seem, they had once a more powerful effect than either the Philippics of Demosthenes or Cicero; and contributed not a little towards the great revolution in 1688." It was played by the Williamites (followers of William of Orange who became William III of England) during the Irish War of 1689–1691 and very probably at the battle of the Boyne, according to Winstock (1970). Johnson (Stenhouse ed.) asserts that the tune was derived from "Jumping Joan" (AKA "Joan's Placket is Torn"), but Bayard (1981) and Glen disagree.

The English composer Henry Purcell has sometimes been credited with the tune, often described as one of his harpsichord lessons. He also used it in his stage work The Gordian Knot Untyed. It was ascribed to him by Playford (1689) and especially later by Chappell (1859), but other musicologists believe there is little direct evidence for this and it is more likely that it was a simply a folk tune; Kidson (1922) states simply the tune was arranged by Purcell for a printing in 1686. Dancing master Thomas Bray included it as the bass in the melody for his country dance "Short and Sweet (3)," printed in Thomas Bray's Country Dances (1699, p. 32). There can be no doubt the tune was well-known in the 17th century, as it is referenced in period literature. Emmerson (1971), for example, reports a description from 17th century literature of a scene in London:

Some were dancing to a bagpipe; others whistling to a Base Violin, two Fiddlers scraping Lilla burlero, My Lord Mayor's Delight, upon a couple of Crack'd Crowds.

Regarding the lyrics, Chapell reports they were ascribed to Lord Wharton and Lord Dorset, but he thinks neither likely to have written them. The words satirize the Irish Jacobite Richard Talbot, Duke of Tyrconnell, and King James' agent in Ireland who was a key figure in the intrigues for returning James to power and involving the French in the struggle for Irish freedom (he ended his life as an exile in France).

Though the song appears in numerous publications, Chappell found the earliest printing to be in a collection called The Muses' Farewell to Poetry and Slavery (1689). There is an old song called "There Was an Old Fellow at Waltham Cross" that uses a combination of strains sounding like both "Lillibulero" and "Dargason;" "Waltham Cross" was published in 1640 and Bayard (1981) thinks this suggests evidence of the existence of both "Lillibulero" and "Dargason" before the 1680's.

Early versions of the air were published in Henry Playford's The Second Part of Music's Handmaid (1689 as "A new Irish tune"), Robert Carr's The Delightful Companion, or Choice New Lessons for the Recorder or Flute (1686), set for keyboard by Purcell in Musick's Handmaid (1689 as "A new Irish tune"), D'Urfey's Pills to Purge Melancholy, as the bass of 'Jig' in The Gordian Knot Untied (1691) and John Gay's The Beggar's Opera (1729, where it appears under the title "Modes of the court so common are grown (The)") and numerous other ballad operas. Alternate songs set to the tune include "Dublin's Deliverance; or, The Surrender of Drogheda" (Pepys Collection), "Undaunted London-derry; or, The Victorious Protestants' constant success against the proud French and Irish forces" (Bagford Collection), "The Courageous Soldiers of the West" (Bagford Collection), "The Reading Skirmish" (Bagford Collection), "The Protestant Courage" (Roxburghe Collection), and "Courageous Betty of Chick Lane" (Roxburghe Collection).

The version of the words ascribed to Wharton begins:

Ho Brother Teaghe, dost hear de decree?

Lillibulero, bullen a la,

Dat we shall have a new Deputie.

Lillibulero, bullen a la

Lero, lero, Lillibulero,

Lillibulero, bullen a la

Lero, lero, lillibulero

Lillibulero, bullen a la.

In Songs of the British Isles, author Jerry Silverman reports that as late as the American Civil War the English musicologist Francis James Child used the tune for another satire, called "Overtures from Richmond" which ridiculed the Jefferson Davis and the Confederacy.

From at least the 19th century, the air of "Lillibulero" has been attached to the song "The Protestant Boys," by which name it is most commonly known among Orange flute band members in Ireland's north.

The Protestant boys are loyal and true,

Stout-hearted in battle and stout-hearted too,

The Protestant boys are true to the last,

And faithful and peaceful when danger is past,

And oh!, they bear and proudly wear,

The colours that floated o'er many a fray,

Where cannon were flashing and sabres were clashing,

The Protestant boys still carried the day.

See also Welsh violinist John Thomas's c. 1752 variant entered in his music manuscript collection under the title "Bili Bylero"[1].

- ↑ Thomas is sometimes referred to as "Alawon John Thomas", but the Welsh work alawon means 'melodies', as in 'John Thomas's Melodies'.