Annotation:Ça Ira: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (15 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

---------- | |||

---- | {{TuneAnnotation | ||

|f_tune_annotation_title= https://tunearch.org/wiki/Annotation:Ça_Ira > | |||

'''ÇA IRA'''. | |f_annotation='''ÇA IRA'''. AKA and see "[[Downfall of Paris (The)]]." AKA - "Ah! Ça Ira." French, Air and March. The air was printed in John Watlen's '''Celebrated Circus Tunes''' (Edinburgh, 1791) soon after the events of the French revolution; Watlen notes it was "Chanted at Paris, July 14, 1790," a reference to Bastille Day. The actual storming of the Bastille occurred a year prior, on July 14, 1789, but it was commemorated a year later as Fête de la Fédération was held on July 14, 1790, as a way to celebrate the establishment of a constitutional monarchy in France. Glasgow publisher James Aird reprinted Watlen's version of the tune five years later in his '''Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs, vol. 4''' (1796); indeed, Aird reprinted the whole of Watlen's volume without giving credit to the source. Anne Gilchrist ["Old Fiddlers' Tune Books of the Georgian Period", JEFDSS, vol. 4, No. 1, Dec. 1940, p. 21] summarizes: "The old French cotillon tune--a trivial vaudeville air which was brutally changed into the savage "Ça ira" of the French Revolution--is found in its early innocence as a country-dance tune in late 18th century fiddlers' books." | ||

[[File:ira.jpg|340px|thumb|left|]] | |||

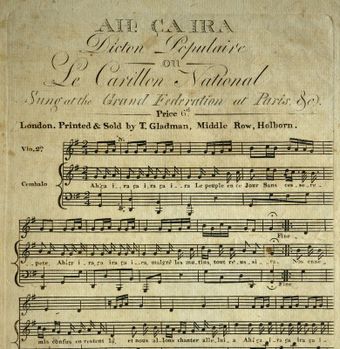

There are pausible but unsubstantiated folklore surrounding the melody. One story goes that Benjamin Franklin, America's emmisary to France, used the expression 'Ça Ira' ("It'll be fine"), repeated and used for the song whose lyrics were said to have been the work of a Parisian street singer named Ladré, around 1790. The melody itself was said to have derived from a composition by Bécour (or Bécourt), a drummer at the Opera. "Ça Ira" is also said to have been set to a tune called "Carillon National," with the irony that Marie Antoinette liked to strum it on her harpsicord (there is a dance in French-Canadian tradition called "Carillon National"). | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

"Ça Ira" [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%87a_Ira], played as a march, was adopted by the West Yorkshire Regiment of the British army as their regimental march. David Murray, writing in '''Music of the Scottish Regiments''' (Edinburgh, 1994), gives this account: | |||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

''At the Battle of Famars in May, 1793, the 14th Foot-'' | ''At the Battle of Famars in May, 1793, the 14th Foot-'' | ||

| Line 19: | Line 24: | ||

'''Ça ira' their own.'' (p. 182). <br> | '''Ça ira' their own.'' (p. 182). <br> | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

This seems to have been drawn from an article in '''Pall Mall Magazine''' called "The Romance of Regimental Marches"<ref>Walter Wood, "The Romance of Regimental Marches", '''Pall Mall Magazine, vol. 9''', 1898, pp. 421-430.</ref>, which recorded that "Ça Ira" had: | |||

<blockquote> | |||

''...for more than a century been the quickstep of the gallant old 14th Foot, and the origin of the march-past is a stirring'' | |||

''as it is unique. When, on May 23rd, 1793, the Allied Forces stormed the French camp at Famars, the 14th, finding the'' | |||

''work a little too hot for them, began to fall back, and the prospect of the assailants was but gloomy. The moment was'' | |||

''one of supreme gravity. The English were losing courage, while the Frenchmen were gaining it, and were keeping their'' | |||

''spirits with the music of the "Ça Ira." Suddenly a brilliant thought entered the mind of the colonel of the 14th. He'' | |||

''dashed to the front once more, commanded his band to strike up the Revolutionary air, shouted, "Come on, lads, and'' | |||

''we'll beat 'em to their own damned tune!" and headed his regiment to a final and triumphant assault. From that day'' | |||

''to this the battalions of the West Yorkshire Regiment--the "Old Fighting Fourteenth"--have played the "Ça Ira" as'' | |||

''their quickstep. The story is as stirring as the music; and it moved even the phlegmatic official compiler of the'' | |||

''regiment to say that the feat at Famars was one which added peculiar lustre to the glory of the British arms.'' | |||

</blockquote> | |||

It was a good band indeed that could manage to strike up the enemy's own march on spontaneous demand from an officer in the midst of battle, much less that it could be heard by all who needed to hear it amidst the din of arms. The patriotic hyperbole of the passage above may have something to do with the fact that Great Britain was in the opening months of the Boer War at the time it was written. | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

The following passage is from '''A Contribution to the History of the Huguenots of South Carolina''' (1887) by Samuel Dubose and Frederick Porcher. It describes a country dance in Craven County, South Carolina in the early 1800's: | The following passage is from '''A Contribution to the History of the Huguenots of South Carolina''' (1887) by Samuel Dubose and Frederick Porcher. It describes a country dance in Craven County, South Carolina in the early 1800's: | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

| Line 35: | Line 56: | ||

''dances, everywhere else.'' | ''dances, everywhere else.'' | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

In the mid-1950's French torch singer Edith Piaf recorded a stiring, military-sounding version. | |||

|f_source_for_notated_version= | |||

|f_printed_sources=Aird ('''Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs, vol. 4'''), 1796; No. 103, p. 41. Samuel, Ann & Peter Thompson ('''Twenty Four Country Dances for the Year 1792'''), No. 9. Watlen ('''The Celebrated Circus Tunes'''), 1791, p. 25. | |||

|f_recorded_sources=Maggie's Music MMCD216, Hesperus - "Early American Roots" (1997). | |||

|f_see_also_listing= | |||

}} | |||

'' | |||

'' | |||

Latest revision as of 03:33, 13 July 2023

X:9 T:Ca Ira. Tho24CDs1792.09 M:2/4 L:1/16 Q:1/4=100 C:"81" B:Thompson 24 CDs 1792 Z:Village Music Project, Chris Partington, 1999 & 2017 W:Hands 6 quite around .| the same back again :| lead down the middle and up W:again,& cast off Allemande & right and left :|. K:G G2GA G2GA|G2GAG4|(GABc) (dB)(ed)|(dc)(cB) ~B2A2| G2GA G2GA|G2GAG4|(GABc) (dB)(ec)|B2A2!fine!G4:| B2(dB) (cB)(AG)|F2AF G[DB][B,d][G,g]|B2(dB) (cB)(AG)|\ GABc d4| d2de d2de|d2ded4|(defg) (af)(ba)|(ag)(gf) f2e2| d2de d2de|d2ded4|(defg) afba|f2e2 (3d2e2c2!D.C.! (3B2c2A2|]

ÇA IRA. AKA and see "Downfall of Paris (The)." AKA - "Ah! Ça Ira." French, Air and March. The air was printed in John Watlen's Celebrated Circus Tunes (Edinburgh, 1791) soon after the events of the French revolution; Watlen notes it was "Chanted at Paris, July 14, 1790," a reference to Bastille Day. The actual storming of the Bastille occurred a year prior, on July 14, 1789, but it was commemorated a year later as Fête de la Fédération was held on July 14, 1790, as a way to celebrate the establishment of a constitutional monarchy in France. Glasgow publisher James Aird reprinted Watlen's version of the tune five years later in his Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs, vol. 4 (1796); indeed, Aird reprinted the whole of Watlen's volume without giving credit to the source. Anne Gilchrist ["Old Fiddlers' Tune Books of the Georgian Period", JEFDSS, vol. 4, No. 1, Dec. 1940, p. 21] summarizes: "The old French cotillon tune--a trivial vaudeville air which was brutally changed into the savage "Ça ira" of the French Revolution--is found in its early innocence as a country-dance tune in late 18th century fiddlers' books."

There are pausible but unsubstantiated folklore surrounding the melody. One story goes that Benjamin Franklin, America's emmisary to France, used the expression 'Ça Ira' ("It'll be fine"), repeated and used for the song whose lyrics were said to have been the work of a Parisian street singer named Ladré, around 1790. The melody itself was said to have derived from a composition by Bécour (or Bécourt), a drummer at the Opera. "Ça Ira" is also said to have been set to a tune called "Carillon National," with the irony that Marie Antoinette liked to strum it on her harpsicord (there is a dance in French-Canadian tradition called "Carillon National").

"Ça Ira" [1], played as a march, was adopted by the West Yorkshire Regiment of the British army as their regimental march. David Murray, writing in Music of the Scottish Regiments (Edinburgh, 1994), gives this account:

At the Battle of Famars in May, 1793, the 14th Foot- later the West Yorkshire Regiment-were being attacked by the French, whose band was playing the revolutionary song 'Ça ira':

"Ah, ça ira, ça ira, ça ira,

a la lanterne, les aristos!

Ah, ça ira, ça ira, ça ira,

Les aristocrats, on les pendra!"

The Commanding Officer of the 14th ordered his drummers to strike up 'Ça ira!' and, turning to his men, cried, 'We'll beat them to their won damned tune!" This the 14th did, and made 'Ça ira' their own. (p. 182).

This seems to have been drawn from an article in Pall Mall Magazine called "The Romance of Regimental Marches"[1], which recorded that "Ça Ira" had:

...for more than a century been the quickstep of the gallant old 14th Foot, and the origin of the march-past is a stirring as it is unique. When, on May 23rd, 1793, the Allied Forces stormed the French camp at Famars, the 14th, finding the work a little too hot for them, began to fall back, and the prospect of the assailants was but gloomy. The moment was one of supreme gravity. The English were losing courage, while the Frenchmen were gaining it, and were keeping their spirits with the music of the "Ça Ira." Suddenly a brilliant thought entered the mind of the colonel of the 14th. He dashed to the front once more, commanded his band to strike up the Revolutionary air, shouted, "Come on, lads, and we'll beat 'em to their own damned tune!" and headed his regiment to a final and triumphant assault. From that day to this the battalions of the West Yorkshire Regiment--the "Old Fighting Fourteenth"--have played the "Ça Ira" as their quickstep. The story is as stirring as the music; and it moved even the phlegmatic official compiler of the regiment to say that the feat at Famars was one which added peculiar lustre to the glory of the British arms.

It was a good band indeed that could manage to strike up the enemy's own march on spontaneous demand from an officer in the midst of battle, much less that it could be heard by all who needed to hear it amidst the din of arms. The patriotic hyperbole of the passage above may have something to do with the fact that Great Britain was in the opening months of the Boer War at the time it was written.

The following passage is from A Contribution to the History of the Huguenots of South Carolina (1887) by Samuel Dubose and Frederick Porcher. It describes a country dance in Craven County, South Carolina in the early 1800's:

Nothing can be imagined more simple or more fascinating that those Pineville balls. Bear in mind, reader, that we are discussing old Pineville as it existed prior to 1836. No love of display governed the preparations; no vain attempt to outshine a com petitor in the world of fashion. Refreshments were provided of the simplest character, such only as the unusual exercise, and sitting beyond the usual hours of repose, would fairly warrant. Nothing to tempt the pampered appetite. Cards were usually provided to keep the elderly gentlemen quite, and the music was only that which the gentlemen's servants could produce. The company assembled early. No one ever though of waiting until bedtime to dress for the ball; a country-dance always commenced the entertainment. The lady who stood at the head of the dancers was entitled to call for the figure, and the old airs, Ca Ira, Moneymusk, Haste to the Wedding, and La Belle Catharine were popular and familiar in Pineville long after they had been forgotten, as dances, everywhere else.

In the mid-1950's French torch singer Edith Piaf recorded a stiring, military-sounding version.

- ↑ Walter Wood, "The Romance of Regimental Marches", Pall Mall Magazine, vol. 9, 1898, pp. 421-430.