Annotation:Perfect Cure (The): Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

---- | ---- | ||

<p><font face="garamond, serif" size="4"> | <p><font face="garamond, serif" size="4"> | ||

'''PERFECT CURE, THE''' (An Uile-Íoc). | '''PERFECT CURE, THE''' (An Uile-Íoc). English, Irish; Single Jig. D Major (Kennedy, Raven): G Major (Williamson). Standard tuning (fiddle). AABB. | ||

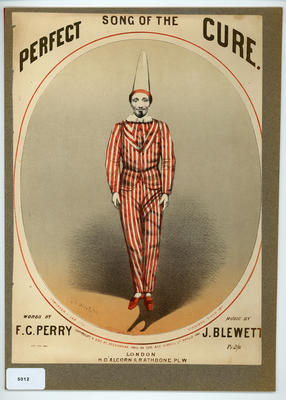

[[File:perfectcure.jpg|300px|thumb|left|]] | [[File:perfectcure.jpg|300px|thumb|left|]] | ||

The tune was originally a ‘novelty jumping song’ (music by J. Blewett) performed by J.H. Stead at various music halls in London, and cites one such venue as Weston’s Music Hall (later the Hackney Empire) in the 1850’s. It was composed as a ‘novelty schottische’, although the dotted duple rhythm has since been altered to triple time (a common enough occurrence in aurally learned traditional music). Burgess writes that the chorus to the song began: “Oh, I’m the Perfect Cure…”, which became a popular expression in Victorian London. Alfred Rosling Bennet, in his 1924 reminiscence '''London and Londoners in the Eighteen-Fifties and Sixties''' [Chapter VI, Street Entertainers] remembered: “About 1860 came Stead with his ‘Perfect Cure’, which raged through the land like an influenza. We had a lot of musical education since then, but what modern composition has rivaled the renown of that to-all-appearance silly production? In later years it was stated that this popular performed was a relative of Mr. ‘Pall-Mall’ Stead” (a reference to the editor of the Pall Mall Gazette from 1883 to 1880, William Thomas Stead). | The tune was originally a ‘novelty jumping song’ (music by J. Blewett) performed by J.H. Stead at various music halls in London, and cites one such venue as Weston’s Music Hall (later the Hackney Empire) in the 1850’s. It was composed as a ‘novelty schottische’, although the dotted duple rhythm has since been altered to triple time (a common enough occurrence in aurally learned traditional music). Burgess writes that the chorus to the song began: “Oh, I’m the Perfect Cure…”, which became a popular expression in Victorian London. Alfred Rosling Bennet, in his 1924 reminiscence '''London and Londoners in the Eighteen-Fifties and Sixties''' [Chapter VI, Street Entertainers] remembered: “About 1860 came Stead with his ‘Perfect Cure’, which raged through the land like an influenza. We had a lot of musical education since then, but what modern composition has rivaled the renown of that to-all-appearance silly production? In later years it was stated that this popular performed was a relative of Mr. ‘Pall-Mall’ Stead” (a reference to the editor of the Pall Mall Gazette from 1883 to 1880, William Thomas Stead). | ||

Revision as of 20:55, 31 October 2015

Back to Perfect Cure (The)

PERFECT CURE, THE (An Uile-Íoc). English, Irish; Single Jig. D Major (Kennedy, Raven): G Major (Williamson). Standard tuning (fiddle). AABB.

The tune was originally a ‘novelty jumping song’ (music by J. Blewett) performed by J.H. Stead at various music halls in London, and cites one such venue as Weston’s Music Hall (later the Hackney Empire) in the 1850’s. It was composed as a ‘novelty schottische’, although the dotted duple rhythm has since been altered to triple time (a common enough occurrence in aurally learned traditional music). Burgess writes that the chorus to the song began: “Oh, I’m the Perfect Cure…”, which became a popular expression in Victorian London. Alfred Rosling Bennet, in his 1924 reminiscence London and Londoners in the Eighteen-Fifties and Sixties [Chapter VI, Street Entertainers] remembered: “About 1860 came Stead with his ‘Perfect Cure’, which raged through the land like an influenza. We had a lot of musical education since then, but what modern composition has rivaled the renown of that to-all-appearance silly production? In later years it was stated that this popular performed was a relative of Mr. ‘Pall-Mall’ Stead” (a reference to the editor of the Pall Mall Gazette from 1883 to 1880, William Thomas Stead).

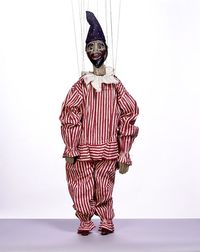

Stead’s performance of the song was remarkable, not so much for his singng, but for the accompanying dance (Stead was known as a dancer). After singing the verse and chorus, he would leap up and down over 400 times with both feet at once. According to ‘Household Words’, a contemporary magazine, Stead could actually perform this jump an astonishing 1,600 times in succession. Not only that, but Stead, like so many music-hall artistes, appeared at three or four theaters in one evening, performing the same act at each! For a short time Stead achieved great fame with his performance of ‘Song of the Perfect Cure’, but his reputation dwindled into obscurity soon afterwards, and in 1886 he died in an attic, a poor man. His song spawned a number of imitations such as "The Reg'lar Cure" and "Love's Perfect Cure," hoping to cash in on the original.

It has been suggested that spirits and other intoxicants (such as laudanum) are ‘the perfect cure.’

Parenthetical to "the perfect cure", Lord Henry Cockburn (1779-1854), in his posthumously published memoir Memorials of His Time (1856), records the following anecdote of the health system of Edinburgh c. 1800 (where each physician seemed to have his own idiosyncratic curatives), and exposes period attempts to extract medical proficiency:

In 1800 the people of Edinburgh were much occupied about the removal of an evil in the system of their Infirmary; which evil, though strenuously defended by able men, it is difficult now to believe could ever have existed. The medical officers consisted at that time of the whole members of the Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons, who attended the hospital by a monthly rotation; so that the patients had the chance of an opposite treatment, according to the whim of the doctor, every thirty days. Dr. James Gregory, whose learning extended beyond that of his profession, attacked this absurdity in one of his powerful, but wild and personal, quarto pamphlets. The public was entirely on his side; and so at last were the managers, who resolved that the medical officers should be appointed permanently, as they have ever since been. Most of the medical profession, including the whole private lecturers, and even the two colleges, who all held that the power of annoying the patients in their turn was their right, were vehement against this innovation; and some of them went to law in opposition to it. (pp. 96-97).

Breathnach styles the melody as a single jig in 12/8 time. It is played as a slide in County Kerry. The first part of the double jig “Long John’s Wedding” and “Long John’s Wedding March” are the same, although the second parts are not. See also the Orkney Islands tune “Rope Waltz (The)” for a tune with similar melodic material.

Source for notated version:

Printed sources: Breathnach (CRÉ IV), 1996; No. 66, p. 33. Kennedy (Fiddler’s Tune Book, vol. 2), 1954; p. 46. Raven (English Country Dance Tunes), 1984; p. 101. Townsend (A Second Collection of English Country Dance Tunes), 1983. Williamson (English, Welsh, Scottish and Irish Fiddle Tunes), 1976; p. 18.

Recorded sources: accordion player James Gannon (Streamstown, County Westmeath) [Breathnach]. Claddagh Records CC56CD, Seán Ó Duinnshléibhe – “Beauty an Oileáin: Music and Song of the Blasket Islands.”

See also listing at:

Jane Keefer’s Folk Music Index: An Index to Recorded Sources []