Annotation:Drop (The): Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m (Text replacement - "garamond, serif" to "sans-serif") |

||

| (17 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[{{BASEPAGENAME}} | =='''Back to [[{{BASEPAGENAME}}]]'''== | ||

---- | ---- | ||

<p><font face=" | <p><font face="sans-serif" size="4"> | ||

'''DROP, THE'''. AKA | '''DROP, THE'''. AKA – "[[Ward's Drop]]." English, Slip Jig. England, Northumberland. B Flat Major. Standard tuning (fiddle). AAB. The melody was printed by John Johnson in his '''Choice Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances, vol. 2''' (London, after c. 1750), and makes several appearances in London publisher John Walsh's collections: '''Caledonian Country Dances''' (London, 17), '''The Third Book of the Compleat Country Dancing-Master''' (London, 1735), and '''The Compleat Country Dancing-Master, Volume the Third''' (London, 1749). It was included in the music manuscript collections of Northumbrian musician William Vickers [http://www.asaplive.com/archive/show_images.asp?id=R0308801&image=1] (1770), and London musician Thomas Hammersley (1790). | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

</font></p> | </font></p> | ||

<p><font face=" | [[File:joshuaward.jpg|200px|thumb|left|Joshua Ward (1685–1761)]] | ||

''Source for notated version'': | <p><font face="sans-serif" size="4"> | ||

The title "The Drop" or "Ward's Drop" (not a drop as we know it, but a dose of half and ounce) refers to the product of a notorious and often cited medical quack of the first half of the 18th century, named Joshua "Spot" Ward (an indelicate nickname that referenced a claret-colored birthmark on his cheek). Ward seems to have originally worked as a drysalter in London, but in 1717 he attempted to represent Marlborough in Parliament, only to be removed when it was discovered he had not received a single vote. He was forced to flee to France (perhaps because of some Jacobite associations) and spent the next sixteen years in that country, perfecting Ward's Pill, which began to received some notoriety as a cure for a variety of aliments. He returned to England around 1733–4, in more advanced circumstances that when he had first left the country. He must have had at least some medical training, for he cured King George's dislocated thumb with a violent wrench, earning some vehement disapprobation in the immediate, but the King's esteem somewhat afterwards. Having secured royal patronage, London aristocracy flocked to his door for ministration. | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

Despite his success with the upper classes, Ward seems to have retained a social conscience for he also ministered to the poor, first with Crown resources, then his own. Ladies of the aristocracy, drawn to his mission, would sit before the doors of his infirmary handing out his medicines to everyone who came. The success made him the object of some professional jealousy, as joked about by Churchill, when asked by Queen Charlotte whether it was true that Ward's medicine made a man mad. "Yes, madam: Dr. Mead" (referring to Richard Mead, M.D., one of the most renowned physicians of his day). | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

Ward advertised that he "performed many marvelous and sudden cures on persons pronounced incurable in several hospitals," and 'proved' his assertions by hiring 'patients' at half a crown a week, instructing them in the symptoms for which he wished to demonstrate a cure, and having them simulate the miracle. Not only the poor were hired, but middle class 'patients' as well, who came in coaches to sit in his consulting rooms (at five shillings a day). His claims to cure gout, rheumatism, scurvy, palsy, "Lues Venera," King's Evil and cancer, were fairly quickly found false, however, and the press started to go to town on him, led by the '''Grub-Street Journal''', which began a crusade against him in November, 1734. | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

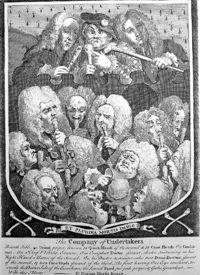

Condemnation in the press was fueled by the fact that Ward's drops and pills were in fact quite dangerous. The '''Journal''' described a dozen cases in which taking the cure had serious, even fatal results. Dr. David Turner reported one individual he treated, who, after taking only one of Ward's pills, "after a most violent vomiting for some Hours, gave near 70 stools, with the most imminent danger." The paper continued the crusade against Ward for several years, documenting case after case. Finally Ward had enough, and took them to court. He failed in his suit, however, as it was thrown out. A quantity of satirical verse and printed doggeral was published, and Ward is referenced in period plays. Ignominy was sealed when William Hogarth depicted Ward with two other notorious quacks in his print "The Company of Undertakers" (a reference to the fatalities from Ward's potions, in which Ward appears with Mrs. Sarah Mapp, bone-setter, and Dr. John Taylor, surgeon and oculist). Boswell, in '''Life of Johnson''', said 'Taylor was the most ignorant man I ever knew, but sprightly; Ward was the dullest.' | |||

</font></p> | |||

[[File:companyofundertakers.jpg|200px|thumb|right|William Hogarth - "The Company of Undertakers," Note Ward at top right, depicted with his discolored face.]] | |||

<br> | |||

<p><font face="sans-serif" size="4"> | |||

Undeterred, Ward continued to practice and dispense his drops and pills, particularly his "Ward's White Drops." He was still treating the poor and other patients past the mid-century mark. Ironically, his 'medicines' survived him, and after his death it was arranged that the profits garnered by their sale would be divided equally between the Asylum for Female Orphans and the Magdalen. The charities benefited greatly at first, until Ward's advertisements and controversy faded from memory, and the potions fell into disuse. The "White Drop," however, continued to be mentioned as late as 1798, when the '''Gentleman's Magazine''' described it as a "good, cheap and useful medicine" (Ward also made medicines in other colors). Ever the self-egrandizer, Ward's will request that his body be buried in Westminster Abbey with national heroes, "within the rails of the altar and as near the altar as may be." | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

What was in the pills? No one knows for sure, as his recipes apparently changed over the years (at least the earlier versions included arsenic). Antimony seems to have been the base for most of them, a fairly commonly prescribed remedy throughout the 18th century. After Ward's death his assistants had no consistent recipes to follow, bedeviling the trustees who were taxed with continuing to manufacture the potions for charity. | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

See also other period Ward tunes: "[[Ward's Pill]]" or "[[Pill (The)]]." | |||

For further information (particularly about literary references), see Marjorie H. Nicholson's article "Wards 'Pill and Drop' and Men of Letters," '''Journal of the History of Ideas''', vol. 29, No. 2 (Apr.–June 1968, pp. 177–196). | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

</font></p> | |||

<p><font face="sans-serif" size="4"> | |||

''Source for notated version'': The 1770 music manuscript collection of Northumbrian musician William Vickers [Seattle]. | |||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

</font></p> | </font></p> | ||

<p><font face=" | <p><font face="sans-serif" size="4"> | ||

''Printed sources'': Seattle (''' | ''Printed sources'': | ||

Johnson ('''A Choice Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances, vol. 2'''), c. 1759; p. 40. | |||

Seattle/Vickers ('''Great Northern Tune Book, part 2'''), 1987; No. 318. | |||

Johnson ('''Caledonian Country Dances'''), c. 1750, p. 71 (as "Ward's Drop"). | |||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

</font></p> | </font></p> | ||

<p><font face=" | <p><font face="sans-serif" size="4"> | ||

''Recorded sources'': <font color=teal></font> | ''Recorded sources'': <font color=teal></font> | ||

</font></p> | </font></p> | ||

| Line 22: | Line 52: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

---- | ---- | ||

[[{{BASEPAGENAME}} | |||

=='''Back to [[{{BASEPAGENAME}}]]'''== | |||

Latest revision as of 12:15, 6 May 2019

Back to Drop (The)

DROP, THE. AKA – "Ward's Drop." English, Slip Jig. England, Northumberland. B Flat Major. Standard tuning (fiddle). AAB. The melody was printed by John Johnson in his Choice Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances, vol. 2 (London, after c. 1750), and makes several appearances in London publisher John Walsh's collections: Caledonian Country Dances (London, 17), The Third Book of the Compleat Country Dancing-Master (London, 1735), and The Compleat Country Dancing-Master, Volume the Third (London, 1749). It was included in the music manuscript collections of Northumbrian musician William Vickers [1] (1770), and London musician Thomas Hammersley (1790).

The title "The Drop" or "Ward's Drop" (not a drop as we know it, but a dose of half and ounce) refers to the product of a notorious and often cited medical quack of the first half of the 18th century, named Joshua "Spot" Ward (an indelicate nickname that referenced a claret-colored birthmark on his cheek). Ward seems to have originally worked as a drysalter in London, but in 1717 he attempted to represent Marlborough in Parliament, only to be removed when it was discovered he had not received a single vote. He was forced to flee to France (perhaps because of some Jacobite associations) and spent the next sixteen years in that country, perfecting Ward's Pill, which began to received some notoriety as a cure for a variety of aliments. He returned to England around 1733–4, in more advanced circumstances that when he had first left the country. He must have had at least some medical training, for he cured King George's dislocated thumb with a violent wrench, earning some vehement disapprobation in the immediate, but the King's esteem somewhat afterwards. Having secured royal patronage, London aristocracy flocked to his door for ministration.

Despite his success with the upper classes, Ward seems to have retained a social conscience for he also ministered to the poor, first with Crown resources, then his own. Ladies of the aristocracy, drawn to his mission, would sit before the doors of his infirmary handing out his medicines to everyone who came. The success made him the object of some professional jealousy, as joked about by Churchill, when asked by Queen Charlotte whether it was true that Ward's medicine made a man mad. "Yes, madam: Dr. Mead" (referring to Richard Mead, M.D., one of the most renowned physicians of his day).

Ward advertised that he "performed many marvelous and sudden cures on persons pronounced incurable in several hospitals," and 'proved' his assertions by hiring 'patients' at half a crown a week, instructing them in the symptoms for which he wished to demonstrate a cure, and having them simulate the miracle. Not only the poor were hired, but middle class 'patients' as well, who came in coaches to sit in his consulting rooms (at five shillings a day). His claims to cure gout, rheumatism, scurvy, palsy, "Lues Venera," King's Evil and cancer, were fairly quickly found false, however, and the press started to go to town on him, led by the Grub-Street Journal, which began a crusade against him in November, 1734.

Condemnation in the press was fueled by the fact that Ward's drops and pills were in fact quite dangerous. The Journal described a dozen cases in which taking the cure had serious, even fatal results. Dr. David Turner reported one individual he treated, who, after taking only one of Ward's pills, "after a most violent vomiting for some Hours, gave near 70 stools, with the most imminent danger." The paper continued the crusade against Ward for several years, documenting case after case. Finally Ward had enough, and took them to court. He failed in his suit, however, as it was thrown out. A quantity of satirical verse and printed doggeral was published, and Ward is referenced in period plays. Ignominy was sealed when William Hogarth depicted Ward with two other notorious quacks in his print "The Company of Undertakers" (a reference to the fatalities from Ward's potions, in which Ward appears with Mrs. Sarah Mapp, bone-setter, and Dr. John Taylor, surgeon and oculist). Boswell, in Life of Johnson, said 'Taylor was the most ignorant man I ever knew, but sprightly; Ward was the dullest.'

Undeterred, Ward continued to practice and dispense his drops and pills, particularly his "Ward's White Drops." He was still treating the poor and other patients past the mid-century mark. Ironically, his 'medicines' survived him, and after his death it was arranged that the profits garnered by their sale would be divided equally between the Asylum for Female Orphans and the Magdalen. The charities benefited greatly at first, until Ward's advertisements and controversy faded from memory, and the potions fell into disuse. The "White Drop," however, continued to be mentioned as late as 1798, when the Gentleman's Magazine described it as a "good, cheap and useful medicine" (Ward also made medicines in other colors). Ever the self-egrandizer, Ward's will request that his body be buried in Westminster Abbey with national heroes, "within the rails of the altar and as near the altar as may be."

What was in the pills? No one knows for sure, as his recipes apparently changed over the years (at least the earlier versions included arsenic). Antimony seems to have been the base for most of them, a fairly commonly prescribed remedy throughout the 18th century. After Ward's death his assistants had no consistent recipes to follow, bedeviling the trustees who were taxed with continuing to manufacture the potions for charity.

See also other period Ward tunes: "Ward's Pill" or "Pill (The)."

For further information (particularly about literary references), see Marjorie H. Nicholson's article "Wards 'Pill and Drop' and Men of Letters," Journal of the History of Ideas, vol. 29, No. 2 (Apr.–June 1968, pp. 177–196).

Source for notated version: The 1770 music manuscript collection of Northumbrian musician William Vickers [Seattle].

Printed sources:

Johnson (A Choice Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances, vol. 2), c. 1759; p. 40.

Seattle/Vickers (Great Northern Tune Book, part 2), 1987; No. 318.

Johnson (Caledonian Country Dances), c. 1750, p. 71 (as "Ward's Drop").

Recorded sources: