Template:Pagina principale/Vetrina: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

<div style="text-align: justify; margin-left: 0pX; margin-right: 0px;"> | <div style="text-align: justify; margin-left: 0pX; margin-right: 0px;"> | ||

{{break}} | {{break}} | ||

[[File: | [[File:Carroll County Blues.jpg|200px|thumb|left|Don Richardson]] | ||

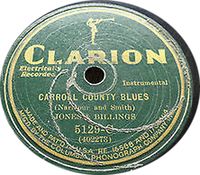

"Carroll County Blues" was the Mississippi fiddle and guitar duo Narmour and Smith's biggest hit recording. The original melody is said to have been composed by fiddler Will Narmour (1889-1961) and was named for his home county, Carroll County, north-central Mississippi, but whether Narmour actually composed it is in dispute. Narmour, however, did record the tune with a man named Shell (Sherril) Smith, whose wife, it has been written, recalled that Narmour may have heard the tune either being whistled by a black farmer (according to David Freeman), or hummed by a black field hand (remembers Henry Young). This farmer claimed authorship and called the tune "Carroll County Blues." Narmour and Smith then "worked the tune out," presumably meaning that they arranged it for fiddle and guitar. Narmour is known to have been friendly with black bluesman Mississippi John Hurt, who lived in nearby Avalon. It has also been maintained, ostensibly by older community members in Avalon, that Narmour's mentor, Gene Clardy, an older local fiddler, was the one who composed "Carroll County Blues." However, the story about the black farmer is also disputed, and, further, it may be that Gene Clardy neither wrote nor played the tune. | |||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

Gary Stanton, in his article "All Counties Have Blues: County Blues as an Emergent Genre of Fiddle Tunes in Eastern Mississippi" ('''North Carolina Folklore Journal''', vol. 28, no. 2, Nov. 1980), points out that the tune is not what one would consider to be in conventional twelve or sixteen bar blues, but was rather built on several 'riffs' (melodic statements) separated by long held notes or a contrasting musical figure. This results in a piece which has alternations of motion and repose, that Stanton contrasts with Anglo-American fiddling, which is almost constant melodic and rhythmic motion. Joseph Scott points out that: | |||

< | <blockquote> | ||

''It seems to be fairly widely accepted among old time music enthusiasts'' | |||

''that Narmour and Smith's "Carroll County Blues" is not a "true blues,"'' | |||

''because it does not use the "standard" 12-bar blues progression. That '' | |||

''reasoning rests on the anachronistic assumption that all "true blues" by '' | |||

''definition used the 12-bar approach. The famous 'standard' 12-bar approach '' | |||

''increasingly dominated within blues over the decades... "Carroll County Blues"'' | |||

'' is based on the same basic progression, the 8-bar I-I-I-I-IV-IV-I-I, as were '' | |||

''some 'Blues' by 'black' Mississippi musicians born around the same era, such '' | |||

''as "Sundown Blues by Alec Johnson, "Pretty Mama Blues" by Cannon's Jug '' | |||

''Stompers, and "Vicksburg Blues" by Scott Dunbar.'' | |||

</blockquote> | |||

In addition the tune features 'blues notes', flattened thirds and sevenths slurred into the natural note. The timing is rather odd (ten measures in the 'A' part instead of the usual eight, among other irregularities) with respect to the majority of fiddle tunes, but despite this Freeman (1975) says it has become one of the most famous fiddle tunes in the United States. He notes it was mentioned in Talking Machine World, an old trade paper, as having been one of the biggest selling records of 1929. Narmour recorded other "Carroll County Blues" tunes (see abc's below) attempting to ride the popularity of "Carroll County Blues #1" but they never achieved such widespread acclaim as the first. Due to its popularity #1 was covered by a great many fiddlers, including Kentuckian Doc Roberts (it appears that the Gennett company gave a copy of Narmour's recording to Roberts and told him to learn it for their next recording session). Subsequently, it has been found in local fiddlers' repertoires throughout the South and Mid-West. As previously mentioned, the 'A' part is irregular, though Phillips notes that Narmour sometimes omits the 2/4 time measures (in an otherwise 4/4 tune) or adds two beats to them, so that his performance can be considered inconsistent as well, a not uncommon phenomenon among traditional fiddlers who seldom play a tune the same way twice. "Carroll County Blues" also seems to be related to bluesman Furry Lewis' "Turn Your Money Green." Other than Narmour & Smith's 1929 recording, another early version was by the Doc Roberts Trio (1933). S' | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

---- | ---- | ||

[[Annotation: | [[Annotation:Carroll County Blues|CARROLL COUNTRY BLUES full Score(s) and Annotations]] and [[Featured_Tunes_History|Past Featured Tunes]] | ||

<div class="noprint"> | <div class="noprint"> | ||

| Line 24: | Line 30: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

---- | ---- | ||

[[File: | [[File:Carroll County Blues.mp3|thumb|left|Carroll County Blues]] {{break|4}} | ||

{{break|4}} | {{#lst:Carroll Country Blues|abc}} | ||

{{#lst: | |||

Revision as of 15:55, 6 July 2019

"Carroll County Blues" was the Mississippi fiddle and guitar duo Narmour and Smith's biggest hit recording. The original melody is said to have been composed by fiddler Will Narmour (1889-1961) and was named for his home county, Carroll County, north-central Mississippi, but whether Narmour actually composed it is in dispute. Narmour, however, did record the tune with a man named Shell (Sherril) Smith, whose wife, it has been written, recalled that Narmour may have heard the tune either being whistled by a black farmer (according to David Freeman), or hummed by a black field hand (remembers Henry Young). This farmer claimed authorship and called the tune "Carroll County Blues." Narmour and Smith then "worked the tune out," presumably meaning that they arranged it for fiddle and guitar. Narmour is known to have been friendly with black bluesman Mississippi John Hurt, who lived in nearby Avalon. It has also been maintained, ostensibly by older community members in Avalon, that Narmour's mentor, Gene Clardy, an older local fiddler, was the one who composed "Carroll County Blues." However, the story about the black farmer is also disputed, and, further, it may be that Gene Clardy neither wrote nor played the tune.

Gary Stanton, in his article "All Counties Have Blues: County Blues as an Emergent Genre of Fiddle Tunes in Eastern Mississippi" (North Carolina Folklore Journal, vol. 28, no. 2, Nov. 1980), points out that the tune is not what one would consider to be in conventional twelve or sixteen bar blues, but was rather built on several 'riffs' (melodic statements) separated by long held notes or a contrasting musical figure. This results in a piece which has alternations of motion and repose, that Stanton contrasts with Anglo-American fiddling, which is almost constant melodic and rhythmic motion. Joseph Scott points out that:

It seems to be fairly widely accepted among old time music enthusiasts that Narmour and Smith's "Carroll County Blues" is not a "true blues," because it does not use the "standard" 12-bar blues progression. That reasoning rests on the anachronistic assumption that all "true blues" by definition used the 12-bar approach. The famous 'standard' 12-bar approach increasingly dominated within blues over the decades... "Carroll County Blues" is based on the same basic progression, the 8-bar I-I-I-I-IV-IV-I-I, as were some 'Blues' by 'black' Mississippi musicians born around the same era, such as "Sundown Blues by Alec Johnson, "Pretty Mama Blues" by Cannon's Jug Stompers, and "Vicksburg Blues" by Scott Dunbar.

In addition the tune features 'blues notes', flattened thirds and sevenths slurred into the natural note. The timing is rather odd (ten measures in the 'A' part instead of the usual eight, among other irregularities) with respect to the majority of fiddle tunes, but despite this Freeman (1975) says it has become one of the most famous fiddle tunes in the United States. He notes it was mentioned in Talking Machine World, an old trade paper, as having been one of the biggest selling records of 1929. Narmour recorded other "Carroll County Blues" tunes (see abc's below) attempting to ride the popularity of "Carroll County Blues #1" but they never achieved such widespread acclaim as the first. Due to its popularity #1 was covered by a great many fiddlers, including Kentuckian Doc Roberts (it appears that the Gennett company gave a copy of Narmour's recording to Roberts and told him to learn it for their next recording session). Subsequently, it has been found in local fiddlers' repertoires throughout the South and Mid-West. As previously mentioned, the 'A' part is irregular, though Phillips notes that Narmour sometimes omits the 2/4 time measures (in an otherwise 4/4 tune) or adds two beats to them, so that his performance can be considered inconsistent as well, a not uncommon phenomenon among traditional fiddlers who seldom play a tune the same way twice. "Carroll County Blues" also seems to be related to bluesman Furry Lewis' "Turn Your Money Green." Other than Narmour & Smith's 1929 recording, another early version was by the Doc Roberts Trio (1933). S'

CARROLL COUNTRY BLUES full Score(s) and Annotations and Past Featured Tunes