Biography:Hugh Gilmour

Hugh Gilmour

| |

|---|---|

| Given name: | Hugh |

| Middle name: | |

| Family name: | Gilmour |

| Place of birth: | |

| Place of death: | Stevenston, Ayrshire |

| Year of birth: | 1758 |

| Year of death: | 1822 |

| Profile: | Composer, Musician |

| Source of information: | http://www.ayrshirehistory.org.uk/Bibliography/pdfs/an14.pdf |

Biographical notes

A church memorial from Hugh's son Robert noted "though blind from infancy a singular gifted…. Died 28th,April 1822, aged 64. Some of his compositions have survived, including a few in the c. 1840's Hamilton's Universal Tune Book (two volumes), edited by James Manson. They include "Earl of Eglinton's Birthday," "Auchincruive House," "Hugh Gilmour's Lament for Niel Gow," "Queen (The)," "Queen's Triumph (The)" and "Kilwinning's Steeple." He is mentioned by James Patterson in his introduction to The Ballads and Songs of Ayrshire (1846, pp. v-vi) in a passage recording the influential musicians of the county in the latter 18th century. Among them was Mathew Hall or Ha', "now upwards of four-score," of Newton-on-Ayr, a cellist. "Mr Hall mentions that he was forty-five years in the habit of frequenting Coilsfield and Eglinton Castle in his capacity as musician. His chief co-adjutor was James M'Lachlan, a Highlander, who came to Ayrshire in a fencible regiment, and was patronized by Lord Eglington (Hugh Montgomerie, himself an accomplished amateur violinist and composer). At concerts at the Castle, the late Earl generally took a part on the violincello or the harp, and amongst other professional players on the violin, blind Gilmour from Stevenston was usually present. "O thae war the days for music!" involuntarily exclaims old Hall..." Evidently Gilmour was known for his opinions as well as his music. John Kelso Hunter (in Life Studies of Character, 1871, p. 121) tells the tale of a Tory candidate who at one time sought to become a Member of Parliament for Ayrshire:

He had heard that a man named Gilmour, a blind fiddler in Stevenston, was in the habit of making Radical speeches; and the said Gilmour had been much respected by the old Earl of Eglinton. This Tory candidate said one day to Eglinton: "My Lord, that old man Gilmour is a dangerous politician, and should not be encouraged." "Well, Blair, you must have a pitiful opinion of the British Constitution when you think that it can be upset by the opinions of a blind fiddler."

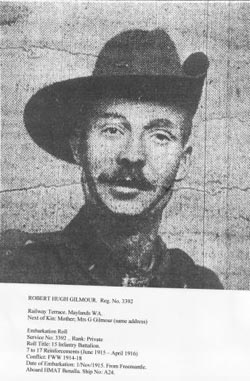

Hugh's son Robert H. Gilmour was an auctioneer in Stevenston, and named his eldest son Hugh, after his father. The younger Hugh Gilmour was born in Stevenson in 1824 and married Mary McGowan in Stevenston in 1846. The young family, with a one year old daughter, emigrated to Sydney, Australia, in 1849. This Hugh Gilmour died in Newcastle, Australia, in 1913. Fiddler Hugh's great-grandson was named Robert Hugh Gilmour. He enlisted as a private in Australia's 15th Infantry Battalion at the age of 30 in World War I and served in France for over two years, where he saw action. He was wounded twice and on the second occasion he was badly gassed. Robert Hugh received a battlefield promotion to Sergeant.

The following article, which mentions prominently Hugh Gilmour, appeared in the Ardrossan and Saltcoats Herald of December 29th, 1860, written by "R.D.":

How the Carpenters of Saltcoats and West Kilbride Gave the Press-Gang the Slip

It is now more than eighty years since the circumstances I am about to narrate occurred and it is somewhere about fifteen years since my grandfather used to relate the story with great glee to a group of young people who sat around the blazing hearth eagerly listening to his funny remarks and anecdotes.

The story commences with the launch of a vessel which took place at Mr. Porter's ship-yard, in Saltcoats, about the year 1789 or 1790, and as launches are generally regarded as auspicious events by carpenters so it was on the present occasion. As was customary then (and I believe is at the present day in Ardrossan) a ball was given to the carpenters in the evening of the same day of the launch, and this evening it was announced to take place in Mr. Campbell's hall. It had just struck five o'clock, and the most of the workers had left the ship-yard and were returning home in order to get prepared for the approaching ball.

Seven o'clock was the hour at which the ball was to commence, but it was long past that hour before the whole company was assembled. About half past past eleven the dancing appeared to be going on in good earnest, and the hall at this moment presented one of the most animated scenes that can possibly be described. On a platform elevated about three feet from the floor sat an old blind man with a fiddle, who showed great dexterity in handling the bow. In one part of the room sat a loving pair talking to each other in the most confidential manner of their prospects of the future, seemingly unconscious of what was going on around them. In another part sat some half-dozen of the fair sex eagerly discussing the merits of some sweetmeats and oranges that had been left them by their admirers as a parting gift, while they had betaken themselves for a short time to another room to enjoy a few minutes chit-chat and a comfortable smoke. In the centre of the floor about fifteen couples tripped it most gracefully on the light fantastic toe; and in another part of the room one might be seen who appeared not to be quite sure whether he should trip in on the crown of his head or the soles of his feet; however in the midst of his reverie his foot caught in the folds of a lady's gown, and he fell flat on the floor to the small amusement of the dancers, as he lay howling out at the full pitch of his voice, "Britannia rules the waves."

The one half of the evening had been spent in this agreeable manner, and all went merry as a marriage bell till about one o'clock, when a private messenger found his way into the hall, and in a somewhat startled manner told one of the carpenters that they had been betrayed by S___, who had given information to the press-gang at Irvine of the night's meeting, and that they now stood outside the door ready to seize them. The looks of the astonished carpenter after receiving this bit of information can be easier imagined than described. For a moment or two he appeared irresolute what to do. However, it was not his own personal safety alone that depended on the issue of events, so he at once communicated the unwelcome tidings to the rest of his comrades, who were not at that time engaged with the dance. The news (not long in circulating through the room) broke upon the ears of the dancers like a thunder bolt. Some regarded it as a trick, but a hasty glance from one of the windows showed there was too much truth in the messenger's statement; others again tried to persuade themselves into the belief that if it came to close quarters they would be more than a match for the gang, and would probably manage to make their escape by overpowering them all at once. But this also was found to be absolutely impossible, as a second glance from the window showed at once that the gang had calculated on meeting with stout opposition, and therefore had increased their numbers threefold nearly.

The quadrille was now stopped when only half finished, and the male dancers stood eyeing each other in the most melancholy aspect; each looking upon his neighbour as able to give some directions as to the course they ought to pursue for the purpose of effecting their escape. At this critical juncture the fiddler, out of all patience at the seeming irregularity of the company, in an authoritative voice ordered them to proceed with the dance, as he didna come here tae fiddle tae folk that could dae naething but talk blethers. A few words from one that now approached the fiddler soon made him aware of what was going on outside, who at the same time told him he might stop his fiddling for the present.

High Gilmour (for that was the fiddler's name), after thinking for a minute, suddenly snatched up his fiddle again, and began to play upon it most vigorously, as if nothing of any consequence had occurred. All eyes were now directed to Gilmour at this sudden outburst of the music again, and one in rather an angry tone demanded what he meant? Gilmour, on hearing this, mad a motion with his head for the man to advance closer to him, which being done--Frien, said Gilmour, addressing the speaker, whatever chance there may be in gettin aff clear, depend on't your chance is no worth a fig if the fiddlin and noise should stop. Let the women carry on the dance wi as much noise as possible, and you, gang your wa's back tae the rest o' your companions an think owre matters as fast as ye can. They'll never jalouse outside that ye ken they're there. Noo awa', an whatere ye ha' tae dae or sae, dae it quickly, and mind ye slip the bar in the door cannily. Noo hoogh! hurrah! on wi the dance.

The fiddler's advice was conveyed to about eight or nine young women, who at once seeing the force and meaning of his words immediately started the dancing, and commenced to shout and stamp with their feet in such a manner as would have done credit to the inmates of bedlam; for what purpose we presume the most of our readers will understand. Various plans of escape were mentioned by the carpenters, who by this time had gathered together, and left the dancing to their sweethearts. One plan was no sooner suggested that it was rejected as being useless.

Every way of escape from the hall they could think of was strongly guarded by a part of the gang, and nothing now appeared for them but to adopt one of the two alternatives--either to allow themselves to be taken quietly, or else to run the risk of a hand-to-hand battle. Twenty-one years on board His Majesty's ship was a term no one was in the least inclined to begin, and they were just on the point of putting the latter alternative into execution (resolving to die before they would be taken), when fortunately, for both parties, one of the young women suggested disguising themselves in their clothing, and so giving the gang the slip. The plan was no sooner proposed than it met with general approbation, and the young ladies now began to strip off as much of their own clothing as they could decently want, and as would properly disguise their respective sweethearts. The dressing of the men was no easy task, and, of course, it had to be performed by the women who were better acquainted with the garments than the men. One woman, of the name of L____, having two brothers and a sweetheart at the ball, and being anxious, if possible, to effect their escape, so disposed of her own clothing that she managed completely to mask the whole three. During this time the dancing never ceased, the women relieving each other by turns as necessity required. All things being now completed, after many a joke and laugh given by both parties, the men, after repeated instructions from the women as to how they should walk, &c., now ventured to open the door, and now for the first time they seemed to notice the gang outside. Of course they had to go through the form of turning back and conveying the sad news in as distressing a manner as they possibly could to those inside so as to set the gang off their guard. As to their presence being now made known, they (the gang) did now care a straw, as they had every way of egress completely guarded. After waiting some considerable time in the hall, the same party issued out, and with counterfeit tears and sobs succeeding in eluding the vigilance of the watch outside, and so passed the whole file, without any remarks, further than that "they were a lot o' lang-legged jades."

After waiting for about an hour or so longer, and as there seemed to be no end to the dance, the gang at last forced the door of the hall, and entered to seize their noble prize. The scene that was presented to the gang on entering the room defies all description--(the nearest approach to it that I can fancy is in a picture of the Dance of the Witches in Alloway Kirk, from Burns' 'Tam o' Shanter', only the bagpipes were used on that occasion instead of the fiddle). The horrified looks of the head of the gang may well be conceived when he found no other persons in the room except Mr. Porter, the shipbuilder; the fiddler, and some thirty young women. It was evident, now, when too late, who the "lang-legged jades" were. He began to curse this one's eyes, and left the hall in a towering rage, cursing his own stupidity, remarking as he left the room, that they might well laugh at him and his men this time, but they would not do it the next.

In concluding my story I may add, for the sake of your female readers, that the women soon after this left the hall, each wearing her sweetheart's jacket, and reached home quite safely, and next morning they visited the retreat of their lovers, and were all very glad to see each other--the carpenters to learn how the affair concluded after they had taken their leave, and if the gang were still in the town; the ladies, on the other hand, were anxious to hear if they had all been able to make their escape good. So after a heary congratulation on both sides, and a good laugh at the success of their scheme, the whole party sat down and partook of some bread and cheese, seasoned with a drop of mountain dew, which had been kindly provided by the ladies for the occasion, and after a few hours of lively conversation, the party separated, seemingly delighted with each other's company.

Further, I may add, that the descendants of the above-mentioned parties can be found at the present day either at Saltcoats or West Kilbride, and no doubt they will remember having heard related the same story in bye-gone years. I only hope if the same should occur that our young townswomen of the present age may display the same amount of courage, and forethought, as was done on the former occasion by their ancestors.