Annotation:Japanese Tommy's Reel: Difference between revisions

*>Move page script |

m (Text replacement - "garamond, serif" to "sans-serif") |

||

| (5 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[{{BASEPAGENAME}} | =='''Back to [[{{BASEPAGENAME}}]]'''== | ||

---- | ---- | ||

<p><font face=" | <p><font face="sans-serif" size="4"> | ||

'''JAPANESE TOMMY'S REEL'''. American, Reel. A Major. Standard tuning (fiddle). AABB. | '''JAPANESE TOMMY'S REEL'''. American, Reel. A Major. Standard tuning (fiddle). AABB. The name of this minstrel performer was perhaps inspired by the phenomenon of The Japanese Embassy to the United States in 1860. Primarily a trade embassy, its purpose was to ratify the new Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation, and followed on Commodore Matthew Perry's opening of Japan in 1854. It was Japan's first diplomatic mission tho the United States. Arriving at San Francisco, the three-man Japanese delegation crossed the Isthmus of Panama by rail, and sailed for Washington D.C., where they were received at the White House by President James Buchanan. After numerous receptions and a grand parade in New York City from up Broadway, the diplomats returned to Japan via the circumnavigation route. | ||

<br> | |||

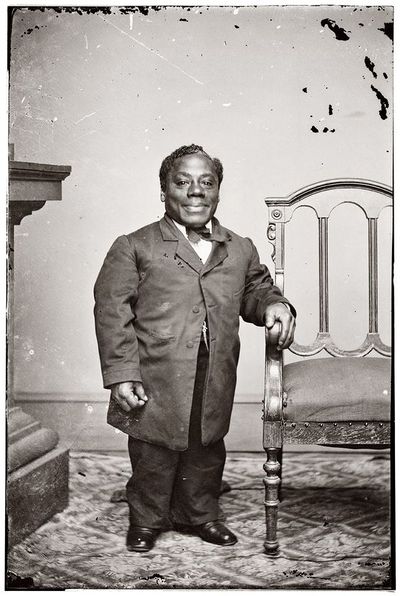

The American minstrel performer Japanese Tommy, aka Thomas Dilward, circa 1860. Brady-Handy Photograph Collection 1840–1902). Tommy performed in the blackface minstrel show and was one of only two known black people to perform with white minstrels before the American Civil War. As a dwarf, his short stature made him a 'curious attraction' and allowed him to perform with white people at a time when practically no black men did. Later he performed with a number of black minstrel | <br> | ||

[[File:Japanesetommy.jpg|400px|thumb|right|Thomas Dilward, AKA Japanese Tommy]] | |||

Began his career with Christy's Minstrels and later played with Bryant's Minstrels, Sam Hague's Georgia Slave Troupe, and Charles Hick's Georgia Minstrels. Thomas Dilward excited and thrilled white audiences with song, dance, and violin.. Also known as the African Dwarf Tommy, he impersonated women on stage. While with Hague's Minstrels in 1870 he assumed the role of a prima donna. He became one of the few African-Americans to work with white minstrel companies. | The American minstrel performer Japanese Tommy, aka Thomas Dilward, circa 1860. Brady-Handy Photograph Collection 1840–1902). Tommy performed in the blackface minstrel show and was one of only two known black people to perform with white minstrels before the American Civil War. As a dwarf, his short stature made him a 'curious attraction' and allowed him to perform with white people at a time when practically no black men did. Later he performed with a number of black minstrel troupes. They referred to Thomas Dilward as “Japanese Tommy” on stage to conceal his identity as an African American and to retain the large white audience base who, ironically, did not want to see a black person performing in black face. | ||

<br> | |||

<Br> | |||

Began his career with Christy's Minstrels and later played with Bryant's Minstrels, Sam Hague's Georgia Slave Troupe, and Charles Hick's Georgia Minstrels. Thomas Dilward excited and thrilled white audiences with song, dance, and violin.. Also known as the African Dwarf Tommy, he impersonated women on stage. While with Hague's Minstrels in 1870 he assumed the role of a prima donna. He became one of the few African-Americans to work with white minstrel companies. | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

HAGUE’S (SAM) GEORGIA SLAVE TROUPE: were organized in Georgia by W. H. Lee in June, 1865. They traveled North and visited Utica, N. Y., in 1866. The party was then and there secured by Sam Hague and sailed for Europe June 16, 1866. They arrived in Liverpool and opened there at the Theatre Royal, July 9. Japanese Tommy, Sam Pride, Mallory, Slatter, Brooker, Neil Solomon, John Graves, Fernando, Johnson, and Jacobs, all colored, were in the party. Lee accompanied them as business manager. A minstrel performance with real Negroes proved a failure and Hague went on a traveling tour, which was anything but successful. After a trial of a few months, Hague advertised in the London papers for a partner; then, after eighteen months, he changed the troupe into a white one, secured St. James Hall, Liverpool, which he opened on October 31, 1870, with but three colored in the party. The compary now consisted of E. D. Beverly, tenor, late of the Pyne and Harrison Troupe; J. E. Johnson, bones; Billy West, tambo; Thomas D. Fenner, interlocutor; Japanese Tommy, Beaumont Read, and J. Carpenter. In December, C. B. Hicks took the bone end. Wilson, Wherry, G. Campbell, Read, Beverly, and T. Medley were the sextette. There were also in the troupe A. Jacobs, Harry Webb, J. Carpenter, George Dolby, Billy Richardson, T. Lott, F. Smith, Aaron Banks, F. Peri, Sheppard, and Clamo. Harry Leslie opened on the bone end May 8, 1871, Hicks closing May 6. M. B. Leavitt opened with this party October 14, 1872, followed on October 21 by Rollin Howard. Eph Horn appeared January 13, 1873. In April two extra end men appeared, making six in all. Johnny Booker opened with them on February 21, 1876. The company opened at the Duke’s Theatre, London, April 10, 1876, for three weeks, then dedicated their new quarters at St. James’ Hall, May 1, 1876, just one year after the fire. After a traveling tour of nine months, Hague’s Minstrels reopened at St. James’ Hall, May 20, 1878. They shortly after took another tour, returning to Liverpool and opening for the winter season on December 2, 1878. | HAGUE’S (SAM) GEORGIA SLAVE TROUPE: were organized in Georgia by W. H. Lee in June, 1865. They traveled North and visited Utica, N. Y., in 1866. The party was then and there secured by Sam Hague and sailed for Europe June 16, 1866. They arrived in Liverpool and opened there at the Theatre Royal, July 9. Japanese Tommy, Sam Pride, Mallory, Slatter, Brooker, Neil Solomon, John Graves, Fernando, Johnson, and Jacobs, all colored, were in the party. Lee accompanied them as business manager. A minstrel performance with real Negroes proved a failure and Hague went on a traveling tour, which was anything but successful. After a trial of a few months, Hague advertised in the London papers for a partner; then, after eighteen months, he changed the troupe into a white one, secured St. James Hall, Liverpool, which he opened on October 31, 1870, with but three colored in the party. The compary now consisted of E. D. Beverly, tenor, late of the Pyne and Harrison Troupe; J. E. Johnson, bones; Billy West, tambo; Thomas D. Fenner, interlocutor; Japanese Tommy, Beaumont Read, and J. Carpenter. In December, C. B. Hicks took the bone end. Wilson, Wherry, G. Campbell, Read, Beverly, and T. Medley were the sextette. There were also in the troupe A. Jacobs, Harry Webb, J. Carpenter, George Dolby, Billy Richardson, T. Lott, F. Smith, Aaron Banks, F. Peri, Sheppard, and Clamo. Harry Leslie opened on the bone end May 8, 1871, Hicks closing May 6. M. B. Leavitt opened with this party October 14, 1872, followed on October 21 by Rollin Howard. Eph Horn appeared January 13, 1873. In April two extra end men appeared, making six in all. Johnny Booker opened with them on February 21, 1876. The company opened at the Duke’s Theatre, London, April 10, 1876, for three weeks, then dedicated their new quarters at St. James’ Hall, May 1, 1876, just one year after the fire. After a traveling tour of nine months, Hague’s Minstrels reopened at St. James’ Hall, May 20, 1878. They shortly after took another tour, returning to Liverpool and opening for the winter season on December 2, 1878. | ||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

One of the earliest troupes to leave the States came to Liverpool in 1866 from Macon, Georgia, and was known as Sam Hague's Original Georgia Slave Troupe. Hague, a native of Sheffield, England, had gone to the United States before the Civil War as a clog dancer. After a mixture of modest successes and failures, he was traveling with a small white minstrel company of his own when he came upon an organized group of ex-slave entertainers. His expansive claims seem to give him somewhat more credit than he deserves. The company which he claims to have organized appears to have been one put together by the ex-slave Charles Hicks. Hicks, on one of his two tours of Australia and New Zealand, 1877 and 1888, spoke of having been with Hague in England. As yet, however, I have not found his name listed among the principals .. inasmuch as Hague wanted the men to dress as slaves both on and off the stage, as well as work like slaves, there is little wonder that the strong-minded, egocentric Hicks, with his clearly articulated leadership attributes, did not stay with Hague. Consider the fact that Hague's programs boasted of comic Abe Cox singing "The Hen Convention upwards 1000 consecutive nights". | One of the earliest troupes to leave the States came to Liverpool in 1866 from Macon, Georgia, and was known as Sam Hague's Original Georgia Slave Troupe. Hague, a native of Sheffield, England, had gone to the United States before the Civil War as a clog dancer. After a mixture of modest successes and failures, he was traveling with a small white minstrel company of his own when he came upon an organized group of ex-slave entertainers. His expansive claims seem to give him somewhat more credit than he deserves. The company which he claims to have organized appears to have been one put together by the ex-slave Charles Hicks. Hicks, on one of his two tours of Australia and New Zealand, 1877 and 1888, spoke of having been with Hague in England. As yet, however, I have not found his name listed among the principals .. inasmuch as Hague wanted the men to dress as slaves both on and off the stage, as well as work like slaves, there is little wonder that the strong-minded, egocentric Hicks, with his clearly articulated leadership attributes, did not stay with Hague. Consider the fact that Hague's programs boasted of comic Abe Cox singing "The Hen Convention upwards 1000 consecutive nights". | ||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

Moreover, Hague's paternalism must surely have been unbearable for peopie so newly independent who were trying to find themselves in an entirely different climate and culture. Something of this is reflected in the attitude expressed in Minstrel Memories, the autobiography of another English minstrel: "All the negroes who wanted to go home he sent back to Georgia at great expense to himself ..." That number could not have been large because seventeen of the original twenty-six are buried in Liverpool, and we can account for at least three more. Harry Reynolds, the author of Minstrel Memories, continues by asserting that "the remaining coloured men in the Company were evidently out to make an impression on the Britisher judging from the pattern and cut of their clothes and their liberal display of jewelry - a tangible proof ... of Sam Hague's liberality. But one sad fact must be related: these poor coloured men, unused to the temptation of our so-called civilization, succumbed, and the fast and dissipated life they led soon thinned their ranks, and notwithstanding the fatherly interest he took in (163) them, Sam Hague lost all control over them and, free from restraint, they soon killed themselves." One is forced to ask if it is really so strange that men from a system of dependency in the heat of South Georgia, thrust into the cold houses of Liverpool, and worked for years without a day off would die early. For the record, one of them, Thomas Dilward, a dwarf known as Japanese Tommy, turned up very much alive in Australia, where he worked both with the Hicks Company and with the white one of Kelly and Leon, after which he returned to England. Moreover, Abe Banks was still with Sam Hague in the early 1880s. However untrue some of the information and assessments are, and however inaccurately some of the attitudes may have been described, they do set up a basis for later comparisons. | Moreover, Hague's paternalism must surely have been unbearable for peopie so newly independent who were trying to find themselves in an entirely different climate and culture. Something of this is reflected in the attitude expressed in Minstrel Memories, the autobiography of another English minstrel: "All the negroes who wanted to go home he sent back to Georgia at great expense to himself ..." That number could not have been large because seventeen of the original twenty-six are buried in Liverpool, and we can account for at least three more. Harry Reynolds, the author of Minstrel Memories, continues by asserting that "the remaining coloured men in the Company were evidently out to make an impression on the Britisher judging from the pattern and cut of their clothes and their liberal display of jewelry - a tangible proof ... of Sam Hague's liberality. But one sad fact must be related: these poor coloured men, unused to the temptation of our so-called civilization, succumbed, and the fast and dissipated life they led soon thinned their ranks, and notwithstanding the fatherly interest he took in (163) them, Sam Hague lost all control over them and, free from restraint, they soon killed themselves." One is forced to ask if it is really so strange that men from a system of dependency in the heat of South Georgia, thrust into the cold houses of Liverpool, and worked for years without a day off would die early. For the record, one of them, Thomas Dilward, a dwarf known as Japanese Tommy, turned up very much alive in Australia, where he worked both with the Hicks Company and with the white one of Kelly and Leon, after which he returned to England. Moreover, Abe Banks was still with Sam Hague in the early 1880s. However untrue some of the information and assessments are, and however inaccurately some of the attitudes may have been described, they do set up a basis for later comparisons. | ||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

By 1869 the blackface minstrelsy was undergoing a change in Wales. Appearing now to even more acclaim were 'Real Negroes', adapting the 'white blackface' to their own particular needs; that is, Black people applying burnt cork in exaggerated style mimicing and subverting the Welsh adaption of Slave Plantation life. They appeared at Wind Street's Grand Circus building Easter 1869 with Hutchinson and Tayleure's Great American Slave Troupe with Japanese Tommy, not Japanese at all, but a Black dwarf known as the Tom Thumb of Africa. The company contained 16 'Real Negroes from the Plantations of America', making 26 Black performers in all. It has to be noted that the Real Negroes arrived only three years after the end of the American Civil War. | By 1869 the blackface minstrelsy was undergoing a change in Wales. Appearing now to even more acclaim were 'Real Negroes', adapting the 'white blackface' to their own particular needs; that is, Black people applying burnt cork in exaggerated style mimicing and subverting the Welsh adaption of Slave Plantation life. They appeared at Wind Street's Grand Circus building Easter 1869 with Hutchinson and Tayleure's Great American Slave Troupe with Japanese Tommy, not Japanese at all, but a Black dwarf known as the Tom Thumb of Africa. The company contained 16 'Real Negroes from the Plantations of America', making 26 Black performers in all. It has to be noted that the Real Negroes arrived only three years after the end of the American Civil War. | ||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

Hutchinson and Tayleure's acts included performers of Negro Life and Character Chapman and Cushman, who were described as late members of the Original Christy's Minstrel Troupe. Chapman and Cushman were making their first appearance in Swansea and the Cushman half was the Black female singer Carlene Cushman a member of the famous Black Swan Trio. Their programme contained sketches on 'Life in a Virginny Log House 'interspersed with Mirth, Stirring Songs, Stories, Pump and Big Boot Dances, and Break-Down Hornpipes..' | Hutchinson and Tayleure's acts included performers of Negro Life and Character Chapman and Cushman, who were described as late members of the Original Christy's Minstrel Troupe. Chapman and Cushman were making their first appearance in Swansea and the Cushman half was the Black female singer Carlene Cushman a member of the famous Black Swan Trio. Their programme contained sketches on 'Life in a Virginny Log House 'interspersed with Mirth, Stirring Songs, Stories, Pump and Big Boot Dances, and Break-Down Hornpipes..' | ||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

Local groups flocked to these shows. The Mumbles Amateur Christy Minstrels jumped on the bandwagon earning rave reviews performing Carry Me Back to Old Virginny, and included Mr. Crapper and Mr. Jones in burnt cork, complete with big drum accompaniment. This profusion of national and local minstrel groups swept the boards of the musical halls and rooms up to and beyond the new century | Local groups flocked to these shows. The Mumbles Amateur Christy Minstrels jumped on the bandwagon earning rave reviews performing Carry Me Back to Old Virginny, and included Mr. Crapper and Mr. Jones in burnt cork, complete with big drum accompaniment. This profusion of national and local minstrel groups swept the boards of the musical halls and rooms up to and beyond the new century | ||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

To make many appearances in Swansea were the famous Sam Hague's Minstrels. Hague himself was an English clog dancer who had become a 'minstrel business manager' while in the USA. His troupe comprised 26 ex-slaves | To make many appearances in Swansea were the famous Sam Hague's Minstrels. Hague himself was an English clog dancer who had become a 'minstrel business manager' while in the USA. His troupe comprised 26 ex-slaves | ||

performing a portrait of life on the old plantation with their only stage costume consisting of garments identical to those worn in their slavery days. The Welsh were to find Sam Hague's homespun attempts at entertainment not up to the local standard they were used to. Some of Sam Hague's Minstrels had obviously found what was expected of them too hard to stomach with their new-found freedom, and that the deflated Hague was forced to send home to the States those performers who wanted to return. He then employed white professionals in blackface to perform with those Real Negros who had opted to stay on in Britain. | performing a portrait of life on the old plantation with their only stage costume consisting of garments identical to those worn in their slavery days. The Welsh were to find Sam Hague's homespun attempts at entertainment not up to the local standard they were used to. Some of Sam Hague's Minstrels had obviously found what was expected of them too hard to stomach with their new-found freedom, and that the deflated Hague was forced to send home to the States those performers who wanted to return. He then employed white professionals in blackface to perform with those Real Negros who had opted to stay on in Britain. | ||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

It is at this juncture that the course of music tilted on its axis by the arrival in Swansea of the Fisk Jubilee Singers, on a fundraising tour for new campus buildings at their Fisk University in Nashville, inaugurated for the Education of Freed Slaves and their Children. With concert hall authority they sang of the loss of their language and culture through spirituals, or what was described in the press as Wierd Slave Songs. The Welsh, having suffered their own loss of language and identity since the publication of the 1847 Report into the State of Education in Wales, identified with the Jubilee Singers and welcomed their return visits over the next 35 years. | It is at this juncture that the course of music tilted on its axis by the arrival in Swansea of the Fisk Jubilee Singers, on a fundraising tour for new campus buildings at their Fisk University in Nashville, inaugurated for the Education of Freed Slaves and their Children. With concert hall authority they sang of the loss of their language and culture through spirituals, or what was described in the press as Wierd Slave Songs. The Welsh, having suffered their own loss of language and identity since the publication of the 1847 Report into the State of Education in Wales, identified with the Jubilee Singers and welcomed their return visits over the next 35 years. | ||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

By 1877, John Russell Bartlett suggested a Japanese influence. The 4th edition of Dictionary of Americanisms includes a definition of an earlier spelling of 'hunky-dory': | By 1877, John Russell Bartlett suggested a Japanese influence. The 4th edition of Dictionary of Americanisms includes a definition of an earlier spelling of 'hunky-dory': ''Hunkidori''. Superlatively good. Said to be a word introduced by Japanese Tommy and to be (or to be derived from) the name of a street, or bazaar, in Yeddo [a.k.a. Tokyo]. | ||

<br> | |||

Hunkidori. Superlatively good. Said to be a word introduced by Japanese Tommy and to be (or to be derived from) the name of a street, or bazaar, in Yeddo [a.k.a. Tokyo]. | <br> | ||

Japanese Tommy was the stage name of the variety performer Thomas Dilward, popular in the USA in the 1860s - and conspicuously not Japanese. Dilward was a black dwarf before cosmologists ever thought of the term. | Japanese Tommy was the stage name of the variety performer Thomas Dilward, popular in the USA in the 1860s - and conspicuously not Japanese. Dilward was a black dwarf before cosmologists ever thought of the term. | ||

<br> | |||

There is no direct evidence to support Bartlett's supposition. It is highly unlikely that Thomas Dilward ever visited Japan, but he may have popularised the expression which he could have picked up from those who had. Commodore Matthew Perry had opened up trade with the country in the 1850s and there were frequent voyages between the US and Japan by | <br> | ||

There is no direct evidence to support Bartlett's supposition. It is highly unlikely that Thomas Dilward ever visited Japan, but he may have popularised the expression which he could have picked up from those who had. Commodore Matthew Perry had opened up trade with the country in the 1850s and there were frequent voyages between the US and Japan by the 1860s. | |||

The Japanese term 'honcho-dori' means something like 'main street' and many cities there have one. US sailors would have known the word 'hunky' and could have added the Japanese word for road ('dori') as an allusion to the 'easy street' they found themselves in in Japan. There certainly were 'honcho-dori' streets of easy virtue in Tokyo and Yokohama that catered for the age-old requirements of sailors in port after a long voyage. | <br> | ||

<br> | |||

Advertisement in the Lewiston Evening Journal of Sept. 14, 1871, shows him as part of the Morris Brother's Minstrels, a large | The Japanese term ''honcho-dori'' means something like 'main street' and many cities there have one. US sailors would have known the word 'hunky' and could have added the Japanese word for road (''dori'') as an allusion to the 'easy street' they found themselves in in Japan. There certainly were ''honcho-dori'' streets of easy virtue in Tokyo and Yokohama that catered for the age-old requirements of sailors in port after a long voyage. | ||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

Advertisement in the Lewiston Evening Journal of Sept. 14, 1871, shows him as part of the Morris Brother's Minstrels, a large traveling organization. "Also the first appearance of JAPANESE TOMMY in five years, he having been engaged in Europe by the Morris Bros. at the enormous salary of $200 PER WEEK IN GOLD. Japanese Tommy will appear at each performance in his ''Great Specialties''." | |||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

</font></p> | </font></p> | ||

<p><font face=" | <p><font face="sans-serif" size="4"> | ||

''Source for notated version'': | ''Source for notated version'': | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

</font></p> | </font></p> | ||

<p><font face=" | <p><font face="sans-serif" size="4"> | ||

''Printed sources'': Buckley ('''Buckley's New Banjo Method'''), 1860; p. 76. | ''Printed sources'': Buckley ('''Buckley's New Banjo Method'''), 1860; p. 76. | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

</font></p> | </font></p> | ||

<p><font face=" | <p><font face="sans-serif" size="4"> | ||

''Recorded sources'': <font color=teal></font> | ''Recorded sources'': <font color=teal></font> | ||

</font></p> | </font></p> | ||

| Line 55: | Line 69: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

---- | ---- | ||

[[{{BASEPAGENAME}} | =='''Back to [[{{BASEPAGENAME}}]]'''== | ||

Latest revision as of 13:29, 6 May 2019

Back to Japanese Tommy's Reel

JAPANESE TOMMY'S REEL. American, Reel. A Major. Standard tuning (fiddle). AABB. The name of this minstrel performer was perhaps inspired by the phenomenon of The Japanese Embassy to the United States in 1860. Primarily a trade embassy, its purpose was to ratify the new Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation, and followed on Commodore Matthew Perry's opening of Japan in 1854. It was Japan's first diplomatic mission tho the United States. Arriving at San Francisco, the three-man Japanese delegation crossed the Isthmus of Panama by rail, and sailed for Washington D.C., where they were received at the White House by President James Buchanan. After numerous receptions and a grand parade in New York City from up Broadway, the diplomats returned to Japan via the circumnavigation route.

The American minstrel performer Japanese Tommy, aka Thomas Dilward, circa 1860. Brady-Handy Photograph Collection 1840–1902). Tommy performed in the blackface minstrel show and was one of only two known black people to perform with white minstrels before the American Civil War. As a dwarf, his short stature made him a 'curious attraction' and allowed him to perform with white people at a time when practically no black men did. Later he performed with a number of black minstrel troupes. They referred to Thomas Dilward as “Japanese Tommy” on stage to conceal his identity as an African American and to retain the large white audience base who, ironically, did not want to see a black person performing in black face.

Began his career with Christy's Minstrels and later played with Bryant's Minstrels, Sam Hague's Georgia Slave Troupe, and Charles Hick's Georgia Minstrels. Thomas Dilward excited and thrilled white audiences with song, dance, and violin.. Also known as the African Dwarf Tommy, he impersonated women on stage. While with Hague's Minstrels in 1870 he assumed the role of a prima donna. He became one of the few African-Americans to work with white minstrel companies.

HAGUE’S (SAM) GEORGIA SLAVE TROUPE: were organized in Georgia by W. H. Lee in June, 1865. They traveled North and visited Utica, N. Y., in 1866. The party was then and there secured by Sam Hague and sailed for Europe June 16, 1866. They arrived in Liverpool and opened there at the Theatre Royal, July 9. Japanese Tommy, Sam Pride, Mallory, Slatter, Brooker, Neil Solomon, John Graves, Fernando, Johnson, and Jacobs, all colored, were in the party. Lee accompanied them as business manager. A minstrel performance with real Negroes proved a failure and Hague went on a traveling tour, which was anything but successful. After a trial of a few months, Hague advertised in the London papers for a partner; then, after eighteen months, he changed the troupe into a white one, secured St. James Hall, Liverpool, which he opened on October 31, 1870, with but three colored in the party. The compary now consisted of E. D. Beverly, tenor, late of the Pyne and Harrison Troupe; J. E. Johnson, bones; Billy West, tambo; Thomas D. Fenner, interlocutor; Japanese Tommy, Beaumont Read, and J. Carpenter. In December, C. B. Hicks took the bone end. Wilson, Wherry, G. Campbell, Read, Beverly, and T. Medley were the sextette. There were also in the troupe A. Jacobs, Harry Webb, J. Carpenter, George Dolby, Billy Richardson, T. Lott, F. Smith, Aaron Banks, F. Peri, Sheppard, and Clamo. Harry Leslie opened on the bone end May 8, 1871, Hicks closing May 6. M. B. Leavitt opened with this party October 14, 1872, followed on October 21 by Rollin Howard. Eph Horn appeared January 13, 1873. In April two extra end men appeared, making six in all. Johnny Booker opened with them on February 21, 1876. The company opened at the Duke’s Theatre, London, April 10, 1876, for three weeks, then dedicated their new quarters at St. James’ Hall, May 1, 1876, just one year after the fire. After a traveling tour of nine months, Hague’s Minstrels reopened at St. James’ Hall, May 20, 1878. They shortly after took another tour, returning to Liverpool and opening for the winter season on December 2, 1878.

One of the earliest troupes to leave the States came to Liverpool in 1866 from Macon, Georgia, and was known as Sam Hague's Original Georgia Slave Troupe. Hague, a native of Sheffield, England, had gone to the United States before the Civil War as a clog dancer. After a mixture of modest successes and failures, he was traveling with a small white minstrel company of his own when he came upon an organized group of ex-slave entertainers. His expansive claims seem to give him somewhat more credit than he deserves. The company which he claims to have organized appears to have been one put together by the ex-slave Charles Hicks. Hicks, on one of his two tours of Australia and New Zealand, 1877 and 1888, spoke of having been with Hague in England. As yet, however, I have not found his name listed among the principals .. inasmuch as Hague wanted the men to dress as slaves both on and off the stage, as well as work like slaves, there is little wonder that the strong-minded, egocentric Hicks, with his clearly articulated leadership attributes, did not stay with Hague. Consider the fact that Hague's programs boasted of comic Abe Cox singing "The Hen Convention upwards 1000 consecutive nights".

Moreover, Hague's paternalism must surely have been unbearable for peopie so newly independent who were trying to find themselves in an entirely different climate and culture. Something of this is reflected in the attitude expressed in Minstrel Memories, the autobiography of another English minstrel: "All the negroes who wanted to go home he sent back to Georgia at great expense to himself ..." That number could not have been large because seventeen of the original twenty-six are buried in Liverpool, and we can account for at least three more. Harry Reynolds, the author of Minstrel Memories, continues by asserting that "the remaining coloured men in the Company were evidently out to make an impression on the Britisher judging from the pattern and cut of their clothes and their liberal display of jewelry - a tangible proof ... of Sam Hague's liberality. But one sad fact must be related: these poor coloured men, unused to the temptation of our so-called civilization, succumbed, and the fast and dissipated life they led soon thinned their ranks, and notwithstanding the fatherly interest he took in (163) them, Sam Hague lost all control over them and, free from restraint, they soon killed themselves." One is forced to ask if it is really so strange that men from a system of dependency in the heat of South Georgia, thrust into the cold houses of Liverpool, and worked for years without a day off would die early. For the record, one of them, Thomas Dilward, a dwarf known as Japanese Tommy, turned up very much alive in Australia, where he worked both with the Hicks Company and with the white one of Kelly and Leon, after which he returned to England. Moreover, Abe Banks was still with Sam Hague in the early 1880s. However untrue some of the information and assessments are, and however inaccurately some of the attitudes may have been described, they do set up a basis for later comparisons.

By 1869 the blackface minstrelsy was undergoing a change in Wales. Appearing now to even more acclaim were 'Real Negroes', adapting the 'white blackface' to their own particular needs; that is, Black people applying burnt cork in exaggerated style mimicing and subverting the Welsh adaption of Slave Plantation life. They appeared at Wind Street's Grand Circus building Easter 1869 with Hutchinson and Tayleure's Great American Slave Troupe with Japanese Tommy, not Japanese at all, but a Black dwarf known as the Tom Thumb of Africa. The company contained 16 'Real Negroes from the Plantations of America', making 26 Black performers in all. It has to be noted that the Real Negroes arrived only three years after the end of the American Civil War.

Hutchinson and Tayleure's acts included performers of Negro Life and Character Chapman and Cushman, who were described as late members of the Original Christy's Minstrel Troupe. Chapman and Cushman were making their first appearance in Swansea and the Cushman half was the Black female singer Carlene Cushman a member of the famous Black Swan Trio. Their programme contained sketches on 'Life in a Virginny Log House 'interspersed with Mirth, Stirring Songs, Stories, Pump and Big Boot Dances, and Break-Down Hornpipes..'

Local groups flocked to these shows. The Mumbles Amateur Christy Minstrels jumped on the bandwagon earning rave reviews performing Carry Me Back to Old Virginny, and included Mr. Crapper and Mr. Jones in burnt cork, complete with big drum accompaniment. This profusion of national and local minstrel groups swept the boards of the musical halls and rooms up to and beyond the new century

To make many appearances in Swansea were the famous Sam Hague's Minstrels. Hague himself was an English clog dancer who had become a 'minstrel business manager' while in the USA. His troupe comprised 26 ex-slaves

performing a portrait of life on the old plantation with their only stage costume consisting of garments identical to those worn in their slavery days. The Welsh were to find Sam Hague's homespun attempts at entertainment not up to the local standard they were used to. Some of Sam Hague's Minstrels had obviously found what was expected of them too hard to stomach with their new-found freedom, and that the deflated Hague was forced to send home to the States those performers who wanted to return. He then employed white professionals in blackface to perform with those Real Negros who had opted to stay on in Britain.

It is at this juncture that the course of music tilted on its axis by the arrival in Swansea of the Fisk Jubilee Singers, on a fundraising tour for new campus buildings at their Fisk University in Nashville, inaugurated for the Education of Freed Slaves and their Children. With concert hall authority they sang of the loss of their language and culture through spirituals, or what was described in the press as Wierd Slave Songs. The Welsh, having suffered their own loss of language and identity since the publication of the 1847 Report into the State of Education in Wales, identified with the Jubilee Singers and welcomed their return visits over the next 35 years.

By 1877, John Russell Bartlett suggested a Japanese influence. The 4th edition of Dictionary of Americanisms includes a definition of an earlier spelling of 'hunky-dory': Hunkidori. Superlatively good. Said to be a word introduced by Japanese Tommy and to be (or to be derived from) the name of a street, or bazaar, in Yeddo [a.k.a. Tokyo].

Japanese Tommy was the stage name of the variety performer Thomas Dilward, popular in the USA in the 1860s - and conspicuously not Japanese. Dilward was a black dwarf before cosmologists ever thought of the term.

There is no direct evidence to support Bartlett's supposition. It is highly unlikely that Thomas Dilward ever visited Japan, but he may have popularised the expression which he could have picked up from those who had. Commodore Matthew Perry had opened up trade with the country in the 1850s and there were frequent voyages between the US and Japan by the 1860s.

The Japanese term honcho-dori means something like 'main street' and many cities there have one. US sailors would have known the word 'hunky' and could have added the Japanese word for road (dori) as an allusion to the 'easy street' they found themselves in in Japan. There certainly were honcho-dori streets of easy virtue in Tokyo and Yokohama that catered for the age-old requirements of sailors in port after a long voyage.

Advertisement in the Lewiston Evening Journal of Sept. 14, 1871, shows him as part of the Morris Brother's Minstrels, a large traveling organization. "Also the first appearance of JAPANESE TOMMY in five years, he having been engaged in Europe by the Morris Bros. at the enormous salary of $200 PER WEEK IN GOLD. Japanese Tommy will appear at each performance in his Great Specialties."

Source for notated version:

Printed sources: Buckley (Buckley's New Banjo Method), 1860; p. 76.

Recorded sources: